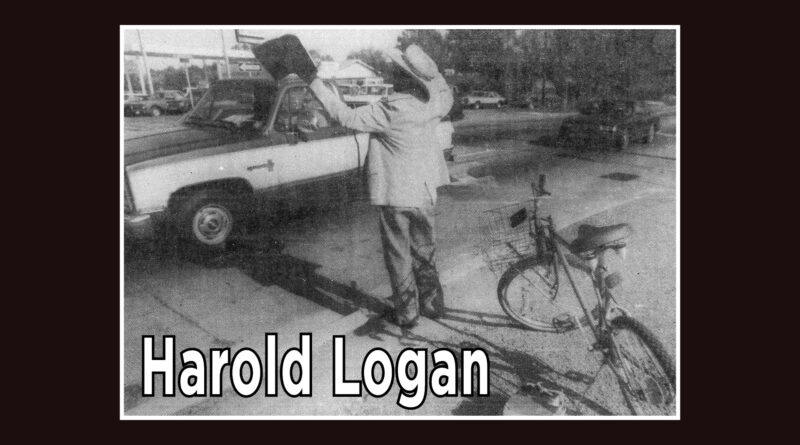

What makes your heart go out ? and the reason behind Harold Logan’s mission in his home town

By HUDSON OLD Journal Publisher

Reprinted from the East Texas Journal April 1995 Edition

Among the mysteries of paradise is the argument that there’s some sort of saintly hierarchy in heaven with rank going those who devote their earthly efforts to the promotion of the Kingdom.

That being the case, a host of minor players will be singing in the choir of the Brother Harold Logan.

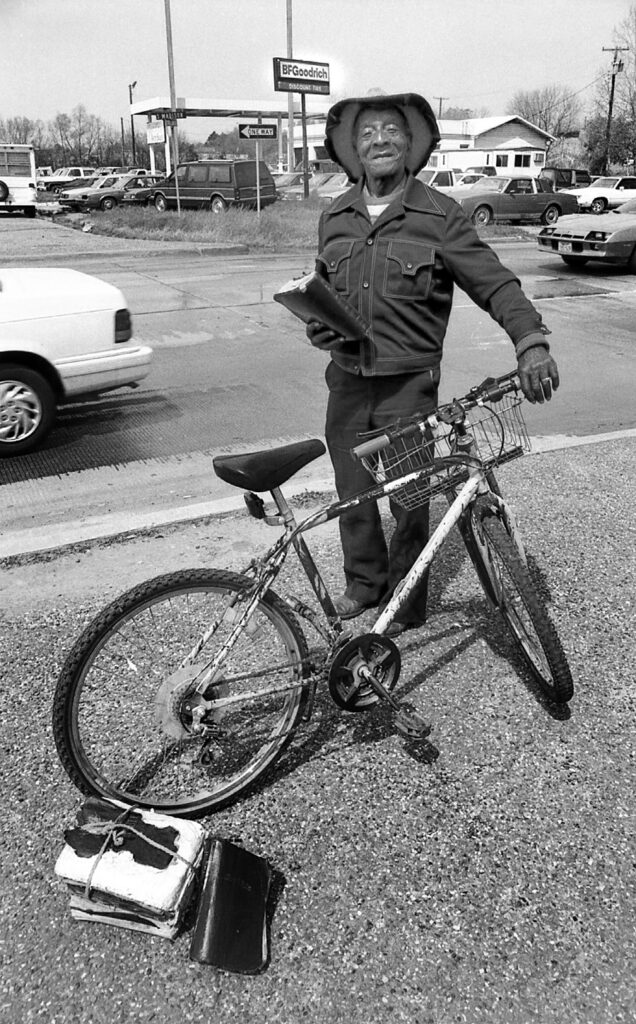

When I was a kid, he already seemed an old man and he was a town fixture, a character playing slide guitar gospel on the street corner, working the frets with the back side of a yellow pocket knife. Forty years later, he was still singing.

He’d given up the guitar, and was as likely to be singing scripture as he was a hymn, making up his own tunes, a song, a song amid the sounds of traffic at the corner of Madison and Ferguson Road.

It was a winter Saturday, years ago now, and the temperature had fallen into the single digit range in keeping with the ice and snow.

When I crossed the tracks on East 1st Street, there was Brother Logan, treading carefully, headed for mass. I slid to a stop and swung open the station wagon.

In addition to an old overcoat, he wore several mufflers so that only his eyes showed beneath the brim of his purple cowboy hat. The hat was plumed with a peacock feather. Brother Logan could be an exotic dresser.

“Oh, you’re as welcome as the flowers in May,” he said.

I forget whether he was wearing the rock that day and in the last few years, I never saw him wearing it at all. Maybe it got too heavy.

The rock was about the size of a softball the last time I saw it, a steadily growing conglomeration of pebbles and stones glued together and worn on a string around Brother Logan’s neck.

“These are things I pick up in my travels,” he explained. His travels took him from mission to mission up a trail leaving from his front door and winding up in Chicago. Traveling, he told me, cut down on his living expenses. His trips lasted for weeks. Chicago enthralled him.

“There’s this one street – I wish you’d go with me sometime just so I can show you all the beautiful churches there,” he once invited. “The chimes peel on Sunday morning – it’s a beautiful sound.”

After church he liked going out for dinner at a Chicago street corner McDonalds.

He was a Titus County native.

The first time he left home, it was going to war.

He made sergeant in an all black platoon of truck drivers.

This wasn’t a glamour job.

As World War II was drawing to a close, after the beach head was established at Normandy, Brother Logan’s job was to run trucks up and down the supply line.

They made a movie about that.

It’s a pretty obscure film called The Red Ball Express.

It’s a couple of hours of army trucks racing across Europe with what’s left of the German Luftwaffe making dive-bomber runs on the supply lines. It was a nice try, but it didn’t work for the Germans. All the same, American casualties were staggering.

When I asked him about the war, he started talking about the trip to Europe.

“There was a sort of a basement on the ship,” he said. “There was a piano in that room and we had the best time. I’d play the piano and me and my men would sing and sing. We sang for days.”

Back when I was a real journalist, intent upon writing “The Harold Logan Story” I interviewed Brother Logan at his old house on Pecan Street.

It sat behind an overgrown fence row. He had a lot of cats.

The floor in the living room sagged beneath mountains of books and Brother Logan sat in a thread-bare over-stuffed chair between the book mountains.

Above him hung a dusty old military group shot, a picture reflecting so many souls it seemed they could fill the bleachers at a high school football field.

Quickly, I established Brother Logan’s military background, jotted notes.

“Could this military background have significant bearing on Brother Logan’s current mental, and therefore economic and sociological standing?” I queried in the frequently silly mind of myself. Onward I interviewed, probing, pulling at strings of man and war.

He remembered hard days for my notes.

And then he wept.

“Something like war,” he whispered. “Something like that makes your heart go out.”

I am less interested in journalism.

For the record, Brother Logan worked for the postal service and lived along the eastern seaboard after the war. Time passed, and Brother Logan noticed that he became less and less useful to the postal service until he noticed himself being of little use at all. He said he wound up in a military hospital where they explained to him that a man whose heart has gone out should relax more, take it easy, go home.

It must have been his relatively early years of being back home that I first remember him playing that slide guitar, street corner gospel.

He’s been faithful to that ministry nearly 30 years now that I know of.

Each day, he comes coast down the long hill on 271 South, gliding into town. He sets up shop where the traffic’s good and just sings to the heavens if the world’s too busy to listen.

Those who roll down their windows while they wait for the light to change can hear a man who loves songs and the words of scripture — King James version — he makes fit the notes he sings.

Sometimes he mixes in some sermon text, exaltations of sheer joy so pure they blew by earthly delight time forgotten ago.

It just makes your heart go out.