Center Point

By Hudson Old

Eastern Camp County, 1948 – It wasn’t that business at Albert Hamilton’s syrup mill wasn’t what it used to be – it was that it was what it had always been.

Neighbors brought sugar cane and traded syrup for processing.

The same as with all communities of rural East Texas farms of the era, cotton was the only cash crop. Most of the cash generated at Center point went for land payments. What was different at Center Point, its citizens weren’t sharecroppers. By the 40’s some were third generation land owners with fourth generation sons and daughters, all connected by the church built as the first public building, dedicated in 1873.

“The community operated the store like a co-op,” said Marvin Hamilton, a West Point graduate descended of a string of Hamilton men who left Camp County for military service. “Uncle Hilton remembers Albert owning stock in the store.”

In 1937, they nearly lost the farm.

“There was a drought,” said Albert’s son, 92-year-old Hilton Hamilton. After losing his draft horses, two colts and a cow to foreclosure, Albert Hamilton left for Oakland, California where there was all the work a man could take, 14 hour days for 18 months in a shipyard.

The first-born son, Hilton at once became a boy doing a man’s work. He lived close enough to walk to the Reynolds Brothers Sawmill where he started stacking out stacking lumber, working the yard.

His value soared and with it his pay, more than doubling from 20 to 45 cents an hour.

When he quit school and refused talk of going back, his mother Annie sent word to Albert.

“I came in one afternoon and he was sitting on the porch,” Hilton said.

“You’re going back to school,” his father told him, “starting tomorrow.”

Albert, Hilton said one time in an army press release written to exemplify the opportunities in a military career, wasn’t a man needing to repeat himself.

“He never believed in telling you to do something a second time without action being taken,” was how the army quoted him in the spring of 1970 when they sent the Pittsburg Gazette news of Captain Hilton Hamilton’s being the lead engineer in Material Management Service at Kelly Air Force Base.

Particularly after his father came back from working the California shipyard where he hadn’t drawn union-scale wages because they said he couldn’t join the union because he couldn’t read the application, Albert Hamilton had resolved that the generation of Hamiltons he and Annie sent out to the world would be educated.

He was hard headed about it.

Later, as a GI slogging through mud up the war-ravaged Korean peninsula for the last 14 months of his 3-year, 8-month military hitch, Hilton earned his GI Bill ticket through engineering school,

Hilton is one of 11 children.

A frugal man, Albert had returned from California with cash enough for lumber to build a new house. The quality of the work made him a contractor, a community builder.

Uneducated he might have been, but he had a touch of common sense genius that Hilton remembers.

“I asked once how he knew how to build a house,” Hilton said. “He said he could see it, that it was complete in his head before he ever started.”

Coming home from a year at Bishop College in Marshall, Hilton volunteered for the army in 1948. After basic he shipped out to Japan, a nation defeated, then supported by the U.S. after World War II.

A country divided, civil war erupted in Korea in the summer of 1950. When the South Korean army gained the upper hand, 200,000 Chinese troops supporting North Korea turned the tide and created an international conflict. The Soviets sent in air support.

America sent its sons.

U.S. troops in Japan were the first to go. When Hilton landed on August 8, 1950, the Americans and South Koreans had been driven south to the edge of the sea where they defending a 32-mile line securing the southernmost toehold on the Korean Peninsula, a battleground named the Pusan Pocket.

They broke out and battled their way to the 38th parallel where the Korean War remains stalled to this day, Hilton remembers as they pushed north seeing the graves, smitterings of crosses marking burials.

“Riding back south on the way home,” Hilton said, “there were fields of them.”

As many Americans died in three years in Korea as died in 11 years in Vietnam, said Hilton’s nephew Marvin, whose father Welton, another of the Hamilton brothers, served two tours in Vietnam.

Welton Hamilton was career military, 30 years. He retired as a full colonel.

“He was a master parachutist with the 82nd Airborne,” said Marvin, one of Welton’s two West Point sons. “He was an airborne ranger. Everything he did, he was high speed. He learned Vietnamese and went to Vietnam first as an advisor. When he went back for his second tour I was old enough that I can remember the sound of explosions and artillery in the background of the tapes he’d send home, recording letters to us. He’d always say it was nothing to worry about, just firing out on the perimeter.”

Colonel Welton Hamilton is buried at Arlington National Cemetery.

Another of Albert and Annie’s sons, Bernard, served in the Air Force.

Their next son, Martenzie, earned the Purple Heart after being wounded in action in Vietnam.

“There’s a story about that,” Marvin said. “At the field hospital, they were going to amputate his leg. One of the surgeons heard the name Hamilton, and that he was from Camp County.”

“I’ll take that one,” said the surgeon, and while prepping for surgery told Martenzie that he’d grown up in East Texas and they figured out that he’d played football against Welton. He saved Martenzie’s leg.

In 1958, Hilton enrolled at Prairie View A&M on the GI Bill, a school where he was “allowed to study engineering.”

Most of the members of his 1961 class of graduating electrical engineers “went to work for the military,” he said.

What happened, though he and his classmates answered aero-space industry want ads advertising no experience needed for a career-track opportunity, applications always required an accompanying photo.

“Once you sent in your picture, you never heard back,” he said. “If you followed up with a call you found out those jobs had been filled.”

Conversely, by the 60’s the military was legally color blind.

After Vietnam, Martenzie followed Hilton’s trail through Prairie View and made a mechanical engineer. Another PV alum, Bernard is a retired architectural engineer.

All of these are stories that Marvin Hamilton heard growing up, when every third year the family returned to Camp County for a reunion.

“I grew up on military bases,” said Marvin. As the son of a combat veteran and officer, “I grew up comfortably middle class, if not affluent in relative terms.”

Military life had only hints of racial discrimination, so little it might be dismissed as ironic comedy.

“There were vendors who wouldn’t sell to black GI’s but they’d sell to Africans on American bases,” Marvin said.

There was one blatant, but understated incident in his adolescence.

They were traveling and stopped for a meal. At the restaurant door, father, wife and son spotted the sign simultaneously – “We reserve the right to serve who we choose,” management advised.

“We should go, Welton,” said Marvin’s mom, Claudette.

“We’ll have dinner,” his father answered, ice cold, and held the door for her.

The service was lousy and nothing was said, but that evening the staff chose to serve the Hamilton family.

“He was a man with bearing,” said Marvin, a student of the ways of his elders.

Here’s how the reunion began.

It was 1966. Martenzie was in the final days of basic training when he got his orders for Vietnam.

By then, Welton was a captain. His mother called.

Before Martenzie shipped out, she wanted the family to gather, and gather at home. Martenzie was only a few hours away, Fort Polk, Louisiana.

She expected Welton to pull strings.

“He tried explaining that wasn’t going to happen,” Marvin said, “that Martenzie was in basic and that nobody gets leave during basic training.”

Annie Hamilton wouldn’t hear it.

Welton gave in and called his battalion commander. Whatever he said worked. His commander called Martenzie’s commander. Whatever he said worked.

“It was something unheard of – he got a pass.

The first reunion, the family sent its next son to war.

With the next reunion they began a tradition, composing a book telling something of the history of the family against the community backdrop of Center Point.

“I loved the stories,” said Marvin, who has become the family historian, the story teller who can take it back to his great grandfather’s days.

Often as not, stories reflected principles, explained expectations.

His Uncle Hilton spoke of boys being sent to break gardens for widows.

“When my dad spoke of riches it wasn’t about money, but character,” said Marvin. Each generation, he says, stands on the shoulders of the last.

Great grandfather George Hamilton provided the foundation, he says. In 1911, he borrowed to buy 160 acres.

“He was strictly business. Life centered around work, improving the land. He was a Mason. He was chairman of the deacon’s committee at church,” Marvin said.

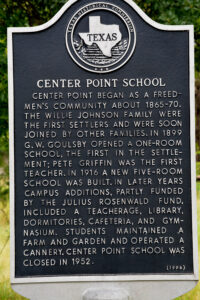

The same year George Hamilton bought land, Christine Cash replaced her husband, Larry Cash, as the new principal at the Center Point School. She and Mrs. G.W. Goulsby began pushing for a four-year high school, according to “O’Center,” a publication of the class of 1928.

“Bond votes provided for a four-room school building constructed in 1916,” as Edgie and Kenneth Reeves recorded in “Center Point School, 1889-1952.”

The first school at Center Point was organized in 1889 by Mrs. Goulsby’s husband, G.W. Goulsby, a blind educator.

In 1916, George was among the men who built the new school.

He died in the Spanish flu epidemic of 1918.

Shortly after, the farm was lost to foreclosure.

His widow remarried and moved to Marietta. In 1933, Marvin’s great grandfather, Albert, and a great uncle discovered provisions of the homestead act. Armed with the law, the family negotiated a settlement for a lien wrongfully taken against a loan after George died.

The lender got back the price of his loan.

Albert and Annie Hamilton came back to Center Point.

Christine Cash continued her own education while serving as principal of the Center Point School. She made the school a center of Center Point life. There were 6,000 books in the library. Curriculum was expanded into vocational trades.

The way Albert and Annie’s daughter Jessye landed work with a newspaper in Kansas city, “I learned to type and take shorthand at Center Point,” she said. At Prairie View, she took a job doing clerical work in the veterans affair office.

“The older brothers and sisters helped with books and tuition for the younger brothers and sisters,” said Brenda Aldridge, daughter of Argie Hamilton-Aldridge, another of the generation who called Annie “Big Mama.” Albert was “Granddaddy” to Marvin and “Big Daddy” to some of the other cousins at reunions.

Students at Center Point paid tuition as they were able. The money kept as many as 10 faculty members, more college-degreed instructors than the county’s common schools.

Students planted gardens. They cut wood for the stove in the cafeteria and the heaters in classrooms. There was a chemistry lab.

Center Point had a brick kiln and a sawmill. The economy included a canning plant that operated like Albert’s syrup mill.

In 1935, Albert was among the Center Point men providing labor to build Center Point’s first dormitory, for girls. A second housed the boys.

Center Point drew students from multiple states, said Hilton, who lived in the last of the days that farm boys helped with the cotton harvest before beginning classes. There was a system for everything.

“On Saturdays I studied with a tutor to stay up,” Hilton said.

Marvin left the military after the Gulf Wars. A West Point degree and an exemplary military record landed him in corporate at Target, in logistics.

The home place at Center Point is in a family trust, owned by shoals of cousins, some less, some more, some who’ve sold and traded shares. Marvin picked up a seven-acre slice at a tax sale, keeping it together.

“It’s sacred land,” said Marvin.

Living less than a day’s drive away, Cousin Brenda, another Hamilton-family Prairie View grad recently retired from a career in the oil business with Saudi Aramco, has recently been appointed secretary of the Center Point Memorial Cemetery Association.

She started this story with a call.

Center Point’s a chapter, a moment in the river of time, a place in the heart of its adherents, an ethos, a way of thinking that should be nurtured and she’s been thinking, imagining ways that might be done.