There’s no business like show business

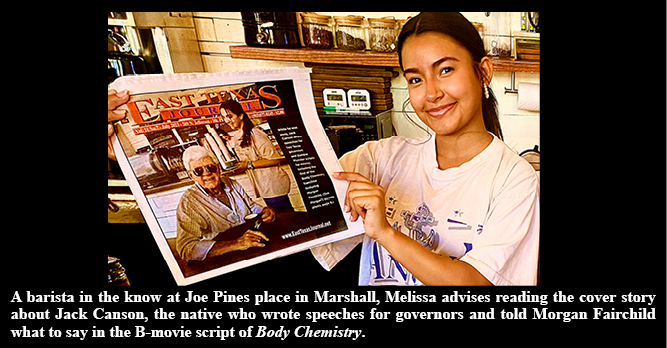

Hollywood veteran Jack Canson skews heavily Silver Fox these days. It’s a role he’s been preparing for his entire life. Full disclosure: I’ve known Jack almost a decade and his exploits could fill volumes. But he’s an unusually humble man and was reluctant to let me tell this little piece of his story. Other than that, everything that follows is all true.

Each year over 50,000 screenplays are registered with the Writers Guild of America. Members of the Guild do this primarily to protect their ideas from being stolen, though the vast majority of them have very little to worry about. Back when Marshall native Jack Canson was hustling scripts in Hollywood under the nom de plume Jackson Barr, he was too busy getting them produced to spend much time worrying about being ripped-off.

The current writers’ strike is mostly about streaming and Artificial Intelligence; when Jack went out on strike as a Guild member in 1988, the issue was video tapes. Technology may evolve but arguments about money don’t. Everybody always wants more of it.

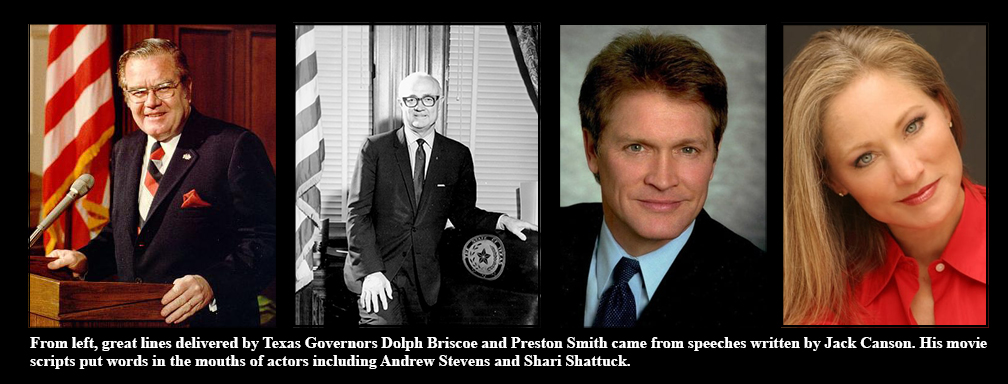

But Jack never missed any meals in Tinseltown and he certainly didn’t arrive in Los Angeles with stars in his eyes. He’d been a successful media and advertising executive for over a decade, written speeches for a couple of Governors and had his work published in national magazines.

In the late seventies Jack Canson and Associates began to hunt bigger game. When his firm beat out Madison Avenue and signed a big contract with the State of California, Jack packed up shop and moved the operation west.

Jack won the job with an advertising campaign that used a snarky, animated crash-test dummy to preach the virtues of seatbelts. Yeah, that was Jack’s. He closed the deal during the lame duck period of one administration, and when he presented the campaign to the new governor’s boys, they hated it.

They shelved Jack’s dummies and a short time later Jack shelved the California Office of Traffic Safety, drifted across town and began writing film scripts. When in Rome.

A few years later some Washington bureaucrat stumbled across Jack’s idea in some old files and the Department of Transportation took the crash-test dummies national. The wildly successful campaign was credited with boosting seatbelt use in the United States ten-fold. You Could Learn a Lot from a Dummy is still considered one of the most effective public service campaigns in US history.

When Washington took credit for the concept Jack took it in stride. But when he discovered they’d licensed his beloved dummies to a toy company Jack threatened to sue. Stealing his idea to save lives was one thing. But if Uncle Sam was getting into the action figure business – Jack wanted his cut.

When the lawyers told him there was no way to pursue the litigation without involving the Transportation Department, Jack wisely decided to settle for an apology and an acknowledgement from the suits on the Ad Council that the whole idea had been his.

“You’ve gotta be pretty stupid to file a lawsuit against an outfit with that many nuclear weapons,” he told me. Jack Canson is no dummy. And besides, if no one’s ever stolen one of your ideas, you’re not really a player anyway.

***

Fewer than five percent of those 50,000 screenplays the Guild dutifully registers each year ever collide head on with a dollar bill. And most that do get sold never become movies. Jack’s scripts have met both fates. He made his first sale when a writing partner snagged a meeting with legendary NFL hall of famer Jim Brown. Jack and his partner were shopping a script they’d written called I was a Negro for the FBI and Brown was running Richard Pryor’s production company.

There was a lot riding on the meeting.

“We both knew it would be a great vehicle for Pryor but were a little apprehensive about the title,” Jack laughed. “But Brown got the whole concept immediately and loved it.”

Pryor got it, too and he signed Jack and his partner on to a development deal with Columbia. Jack became a highly-paid Hollywood screenwriter on his very first sale. Something that happens about once every almost never.

A few months later Pryor self-immolated while freebasing cocaine. The comedian survived (barely) but Jack’s movie didn’t. Despite being one of the biggest paydays of Jack’s career, I was a Negro for the FBI never got made.

Making a living in the creative arts isn’t for everyone, certainly not sissies. Creative people fail professionally in droves. The few who succeed have the will to overcome certain aspects of human nature. Like fear of rejection, fear of starving to death, aspects like that.

In 1987 Jack met Nancy Barr. Nancy was in story development at CAA, the era’s premier A-list talent agency. Jack fell for Nancy and after reading an article of his in The Atlantic, she fell for Jack’s writing. (And soon enough, for Jack.)

With her help Jack sold a screenplay to Julie Corman, the wife of the fabled B-movie producer Roger Corman. The sale was made under the table during the 1988 writer’s walk-out (at five months, the longest in Guild history) because Jack Canson was on strike. Jack borrowed Nancy’s last name and his first screen credit (and the thirteen that followed) listed him as Jackson Barr.

“Nancy taught me the difference between writing a book, which I knew how to do, and writing a screenplay, which I hadn’t necessarily known how to do before we met.” They shared the writing credit.

Nancy and Jack were married in 1989, the year their movie came out. Nowhere to Run was a sensitive and probing look at small-town hypocrisy as seen through the eyes of a group of high school students. It featured David Carradine and Jason Priestly, a red-hot TV star from the era. (Beverly Hills 90210)

Jack had originally titled the piece Caddo Lake and it was loosely based on real events from his teenage years. When the budget wouldn’t allow for a location shoot in the ArkLaTex, Caddo became Malibu. A title change and other reworks of the story followed.

Think about that for a minute.

You dredge up painful memories about the place where you grew up and then spend a year or two turning them into a screenplay. Then someone tells you they’re going to make a movie out of it!

But when the picture comes out, you don’t care for the title, your childhood home has been moved 1,500 miles to the west and dozens of other changes have been crowbarred into the final cut. Seeing your writing credit on the big screen in a movie theatre can be a bittersweet experience.

But a better example of vagary and heartbreak in the creative arts is the one where the guy never sells the script in the first place. In Hollywood you need to be more than strong to survive. You need thick skin, a big brain and – if you want to write – a really big heart. Almost no one fits the bill.

“Nowhere to Run was the first screenplay of mine that was released. Probably my best work.”

Every writer has that one thing.

A short time later Jack “[got] stuck working with Corman.”

Jack paused and said, “I guess I shouldn’t say ‘stuck.’”

Probably not.

Producer Roger Corman, 97, has been signing paychecks in Hollywood for over seventy years. Director like Francis Ford Coppola, Ron Howard and Martin Scorsese have cashed them. Corman’s movies have featured Jack Nicholson, Bruce Dern, Dennis Hopper, Tommy Lee Jones, Sandra Bullock, Robert De Niro and handfuls of other future Oscar winners. Like Jack, scores future legends found themselves stuck working for Roger Corman over the years.

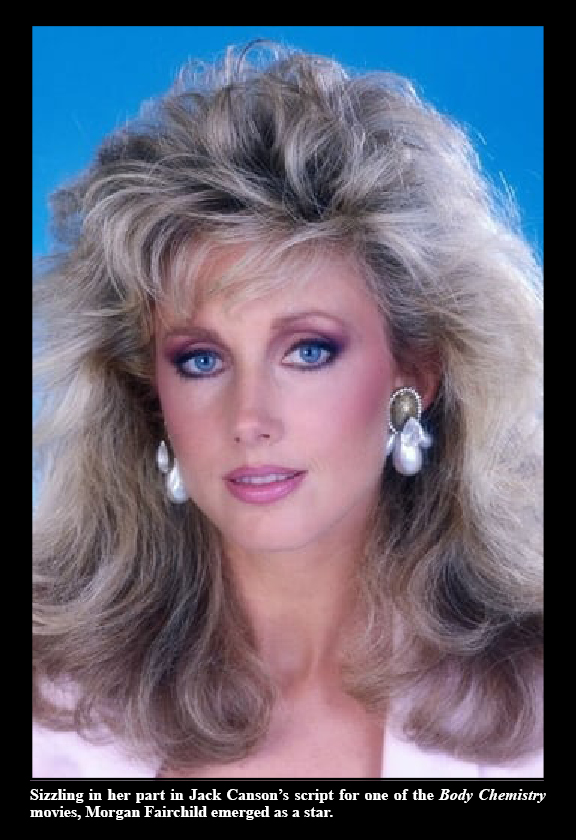

Jack’s association with Corman’s production companies garnered several more screen credits, including a script he wrote for eighties bombshell Morgan Fairchild. Her appearance in 1990’s Body Chemistry II was responsible for millions of Blockbuster rentals by men wanting a closer look at Ms. Fairchild than the one they’d gotten on Dallas. Convinced a movie with the word ‘body’ in its title would deliver, those men came away disappointed.

Jack’s other big customer during those days was an outfit called Full Moon Features, a Corman competitor in the lucrative horror/exploitation space. Full Moon and Corman are still and business, and there’s probably no reason Jack couldn’t have kept cranking out a living in LA for many more years. In less than a decade he’d amassed fourteen feature-film writing credits in a town where most screen writers are actually waiters.

But he quit while he was ahead.

When he got back to East Texas Jack did what he does best: Whatever came next. He worked with Don Henley when the rock star from Linden formed the Caddo Lake Institute, a conservation project that celebrated its thirtieth anniversary this year. Jack still looks after his friend Henley’s boat when the weather kicks up on the lake.

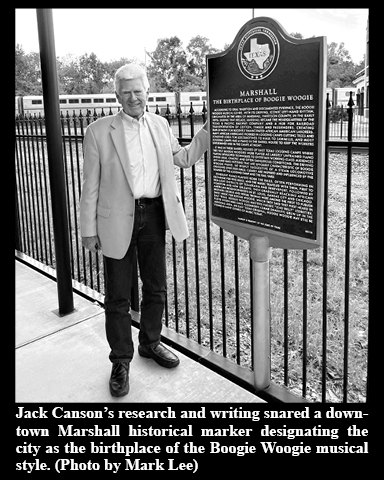

Later, Jack began a lobbying effort amongst a diverse group of stakeholders to have his hometown named as the official birthplace of Boogie Woogie music. You can visit the historical marker down at the train station in Marshall, where a lot of that Boogie Woogie went down back in the day. The Texas Eagle still stops there on its way between Chicago and San Antonio.

“Unlike a lot of the guys I knew who were trying to break into the business, I never had to flip any burgers out there. I got to town with a pretty good piece of business in my pocket and delivered what I’d sold. The dolts in Sacramento didn’t use my idea. But I got paid. And after those big checks came in from the Columbia deal (for the Richard Pryor film that never was) I fell in with Roger and Full Moon for several years and never went hungry,”

Quite the opposite.

Jack’s old boss Roger Corman has been subjected to the moral outrage of PTAs and the probity of PhD dissertations. His movies have been described variously as schlock, groundbreaking, depraved exploitation and treasures of the American Cinema. Whatever else they are, there are over four hundred of them and at least one (The Fall of the House of Usher) wound up in the National Film Registry which, trust me, is an extremely big deal.

***

So, what became of those fourteen movies Jack wrote? In the internet age nothing ever disappears.

“After I left, I didn’t think all that much about my stint in Glitter Gulch. I became way too busy with other stuff. Then, during the pandemic, I start getting calls from people looking for Jackson Barr.”

Was Jack was blowing up in his late seventies? Again?

It seems the Web had introduced a whole new generation of fans to films like Seedpeople and Mandroid (two of Jack’s Full Moon titles). These fast-paced horror-thrillers are populated by utility-infielder monsters and busty victims. Zombies? Androids? Evil Robots? MORGAN FAIRCHILD? The mind of Jackson Barr has dreamed up stories featuring them all.

And before you scoff at the monster & cleavage genre, take a moment to consider what you do for a living. Is it more fun than sitting around all day making up stories about Cyborgs?

“I’ve got another novel ready and I really should start shopping for an agent,” Jack told me as we were wrapping up.

He hasn’t stopped writing since he first held a pencil. There have been more than a few acts in his long career; from Army-man journo in Europe to artist in residence at UT Austin, where Jack was an early recipient of the prestigious Doby Paisano Writing Fellowship.

Before wrapping up the interviews and podcasts on his schedule (the latest one was about Subspecies) and finding an agent for that novel, Jack will likely have already started some new project. Who knows, maybe another screenplay? Jack’s eightieth birthday is just around the corner.

I slow-pitched him the corny line that never fails to elicit an interesting reaction from real showfolk.

“There’s no business, like show business, Jack.”

“Lordy, don’t I know it.” His mischievous grin made it clear the old storyteller’s last act was still a ways into the future.