1st Street Longhorns anchor Scenic Spring Cattle Drive

Reprinted from the March 2019 East Texas Journal Edition

When the vet couldn’t save his bull, Longhorn market conditions minimized the financial impact of losing a calf crop the year Jerry Parr ran his seven-cow herd without a bull until he found one he liked.

“A Longhorn’s worth about half what anything else brings,” said Mr. Parr, “so if a cow misses a calf I just lose half as much.”

A weekend and after-hours stockman, his herds include cattle, rescued donkeys and a stray pig. When half their 50-acre park goes underwater, they retire to the crests of rolling hills.

“The best way to market a donkey is to pay $5 to anybody who’ll take one and provide a good home,” Mr. Parr has found. There’s a neighbor with a secure pen willing to take the pig for no charge.

“The problem is catching the pig,” Mr. Parr said.

The animals shelter in recycled oil field tanks converted to open stables. From fencing to farm equipment, capital improvements on the Parr Place are mostly salvage from Allen Scrap Metal.

Success here is of a philosophical nature. It’s measured in terms of weekend and after-hours therapy. It’s dependent on management with appreciation for donkeys and a heart for strayed pigs. It’s safe sanctuary for Texas Longhorns who’d be extinct in short order if their lives depended on market forces.

The last two 400-pound calves sold at auction averaged a shade under $200 a head.

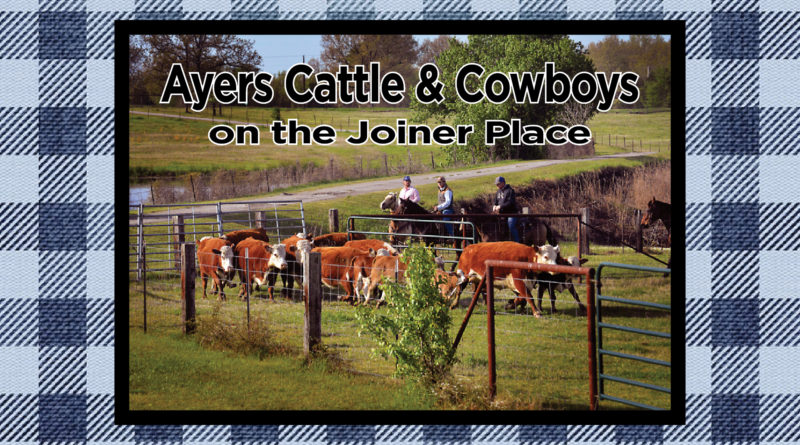

A full-time cattleman with herds spread across five places in two counties, Jimmy Ayers adheres to more traditional business concepts. Buyers interested in a Tigerstripe mama and calf should bring along $2,750 for the pair.

“I know people think I’m nuts,” he said. Fair enough. He understands his price thins out buyers.

Pairs he doesn’t sell go back into a traditional cow-calf operation. Forty years in, Jimmy Ayers has results that speak for themselves.

His cross-bred mamas are out of Brahman bulls on purebred Herefords from the Brite Ranch, an elite herd in Texas cattle lore, a story dating back to 1855.

The Brite Ranch is in Prisidio County, 430 miles south of Amarillo.

“My truck driver said when he turned off the highway it was still twenty nine miles to the pens,” Mr. Ayers said. He bought two 18-wheeler loads of 500-pound heifers six years ago when they were selling off breeding stock in a drought.

Breeding for fertility, longevity, performance and disposition with attention to the distinctively Hereford signature white face and red body, Brite Ranch has a “closed” herd, meaning management doesn’t gamble with the influence of genetics from anything beyond what they raise.

Tigerstripe describes the brindle color of a Hereford-Brahman cross mixing beefier Hereford of English descent with Brahman bulls, a cross producing “a superior cow for the South,” Sara Gugelmeyer said writing for American Hereford’s on-line publication.

The resulting stock is known for “hybrid vigor,” or “Heterosis,” in the academic world beyond the Joiner Place where Mr. Ayers and a team of mounted cowboys worked cattle in March.

Heterosis.

“We can call up my wife if you’re going to need to spell it,” he said. A retired teacher, Darlene Ayers handles spelling for the family, he said.

A work in progress for a week, his roundup on the Joiner place began with successive days of trial runs, opening gates and “baiting” the working pens with feed. Getting his cattle in that groove, before the mid morning arrival of mounted cowboys he penned cattle coming in for breakfast when he called.

Next, the cowboys rode out. Horses knowing their business moved closing ranks of grazing cattle willing to be pushed toward working pens while letting those suspicious of horsemen turn and slip by.

Those penned, the third act blended dogs in the mix. Those dogs were smart. So were the nervous cattle, the herd rebels. They surrendered.

The Ayers family affinity for cattle skipped his father’s generation. Growing up, Jimmy Ayers marked off school days counting down to the freedom of summer days savored with the grandfather who ran cattle in Cass County.

Graduating in 1973, he signed on with Brown and Root, working construction associated with Lone Star Steel. He studied with a workman’s eye before opening his own company, J&R Pipe Services. He provided labor gangs contracted out to the steel mill and in 1980 he bought his first set of seven matching heifers.

Today, cattle feed two generations with son Dustin now signed on for life. The father’s one-liners speak to the passing of years required to put together the leases, pull together the equipment and groom a younger generation of hired cowboys blending with a smaller band of friends showing up as needed because they like it.

He names Tommy Franks and Tony Anshutz as reliable members of a future “Nursing Home Crew.

“Whoever goes in first is responsible for saving a room for whoever checks in last when we’re done,” he said.

Researching and writing for the Noble Research Institute, Dr. Robert Wells describes the enhanced production and durability of Tigerstripes as the heterosis achieved by crossing purebred strains of two complementing breeds resulting in an F-1 cross. He said A&M research showed a 10 to 20 percent increase in the breeding life of F-1’s.

Breeders pitching the efficiency of Tigerstripes include Mike Armitage of Claremore, Oklahoma, interviewed for the American Hereford story. Describing as “hot” the Brahman blood making Tigerstripes tolerant of the heat and humidity of Southern summers, he describes Tigerstripes as good milk producers weaning calves 30 to 50 pounds heavier.

Known for big frames and high-spirited genetics, Brahman influence is often seen in rodeo stock favored for a rodeo attitude.

Mr. Armitage provided another view.

While agreeing the Brahman blood tends to manifest traits suspicious of men on foot, intolerant of four wheelers and generally requiring working facilities more substantial than portable cattle panels, Mr. Armitage said that worked horseback Tigerstripes “can be the simplest cows to handle.”

Mr. Ayers experience leads him to agree with the points on heat tolerance, milking, weaning weights and breeding life while describing Tigerstripe disposition in other terms.

“They’re not the right match for everybody,” he said. “Get one riled and they’re crazy.”

The back side of the Ayers father-son lives as cattlemen is dawn to dark days of summers rolling hundreds of acres of hay including a flagship meadow on the “home” place put together off Texas Highway 49 near the Titus-Morris County line. There they irrigate, growing Tifton Bermuda, a prime strain for hay production. For a time they grew corn, harvested for high protein, high energy silage. They gave it up when they saw plowed land eroding beyond what could be controlled. They put more value on the life in their topsoil than the corn.

The 7-mama Parr Longhorn spread’s about value measured other ways. Underpinned by the third generation of family at Allen Scrap metal, the value of old oil field tanks weighed in as scrap has been demonstrated with their conversion to shelter.

Ask the Longhorns worth less than their upkeep measured in dollars and cents. Talk to the once-homeless pig. No kidding, pull in at the gate and they’ll likely come visit, thinking you might have apples. They’re spoiled as grandkids.

Down by the pool there’s a functionally obsolete horse drawn hay rake with a matching mower. Just inside the gate there’s a growing arrangement of ancient tractors, likewise salvaged.

What we’ve got at the Parr Place on the edge of town is imagination transforming land to a canvass turning salvage to treasure.