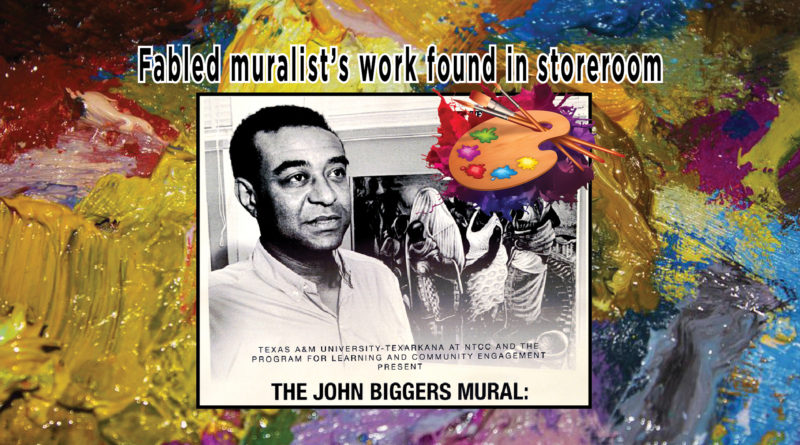

Fabled muralist’s work found in storeroom

An Austrian Jew fleeing the Holocaust in 1938 wound up teaching art in a black trade school in North Carolina. John Biggers gave up his dream of studying plumbing to become a student of Dr. Viktor Lowenfeld.

By the 60’s, John Biggers murals became renowned among the art-world wise and a generation later a Northeast Texas Community College teacher found one of his originals in an elementary school storage room between Naples and Omaha.

This hardly ever happens in Morris County.

The Paul Pewitt school district agreed earlier this year to loan the painting to the community college.

It’s being restored to be displayed in a classroom with a glass wall so that when illuminated at night it can be seen from the admin building parking lot.

Northeast’s Dr. Ron Clinton tells a story about the cultural and global influences shaping the work of the artist who painted “The History of Negro Education in Morris County.”

The painting is named the same as the title of a master’s thesis written by P.Y. Gray from which its elements are drawn.

Mr. Gray was principal of George Washington Carver High when it opened in 1955. Born into slavery in Missouri, emancipated as a child at the close of the Civil War, George Washington Carver was a botanist who published 44 practical bulletins encouraging poor farmers to diversify, to produce a wider variety of food crops that could be stored.

In those days, food supply was a first step in alleviating Black poverty in the Old South.

The artist who painted the picture of Black education in Morris County came to Texas thinking he’d be able to study the work and influence of Mexican muralist Diego Rivera if only he got closer to the Mexican border. Instead of murals, John Biggers found work at Texas Southern, the university in Houston where P.Y. Gray wrote his thesis before returning to teach in Morris County, the world he wanted to change.

He saw education as key in alleviating Black poverty in the Old South.

Dr. John Biggers established the art department at Texas Southern in 1949.

As the new principal of the new Carver High, Mr. Gray got approval to commission his former teacher to turn his thesis into a painting.

So he did.

It’s 25-feet wide.

Dr. Biggers was inspired by Rivera’s murals, stories told in paintings celebrating Mexican culture and covering the walls of public buildings in Mexico.

Murals like that never caught on in the states.

As Dr. Biggers career was coming to life in the 1940’s and 50’s, there were no American artists of note celebrating black history either.

The sharecropping story dominating black life in the south hadn’t changed much in the better part of a hundred years.

Artists in France had the same lack of interest in the bottom rung of the socio-economic food chain a hundred years earlier.

Dr. Clinton’s lecture includes a power point slide show. One slide is a frame of an 1857 oil. “The Gleaners” shows workers in a grain field after the harvest.

“Before Jean-Francois Millet, the life of peasants wasn’t of interest to European artists,” Dr. Clinton said.

Dr. Biggers got it.

The Austrian art teacher he met at Hampton Institute was not a man restrained by convention. Early on a musician, an intellectual with university credentials, Dr. Viktor Lowenfeld once chose to teach sculpting at an institute for the blind in Vienna.

More importantly, he wrote.

He wrote from a background shaped by his study of psychology. He studied blind sculptors and wrote about that. He studied the art of children and connected intentional creativity to mental development. He studied art as it relates to the artist’s culture, to race, to economics and he encouraged his students to think of their art in that way.

He came into America through the back door.

He didn’t apply at Hampton because he wanted to teach a vocational trade.

“He wanted to teach at a black school,” Dr. Clinton said. He was a student of cultures and a powerful force in the unfettering of Dr. Biggers’ brain.

Dr. Lowenfeld served the American Navy during World War II. In 1946 he earned his citizenship and when he took a position at Penn State, Biggers followed. At Penn State, Dr. Lowenfeld’s teaching generated a movement. John Biggers was an early disciple, the student whose work eclipsed his professor at the same time it moved the Austrian’s ideas through America’s art scene from the 1940’s until the 80’s.

In 1943 his work was shown at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

In 1957 his work landed a grant for six months study of the culture and art of West Africa.

Five years of work later, he published “Ananse: Web of Life.” His collection of drawings and writing from Africa won the Dallas Museum Award for best Texas Book Design.

In ’72 he was named a Penn State Distinguished Alumni and in ’81 was given an award by the mayor for work contributed to his adopted Houston hometown.

At the invitation of Dr. Olive “Ollie” Theisen, the founding matriarch of an art program at Northeast, Dr. Biggers came to a re-dedication of his Morris County mural in 1989.

He said there was no greater satisfaction than finding his account of a community story still “alive” after so much time.

“This is why I paint,” he said.

Born to a minister father, early on John Biggers understood the church as both the spiritual and social underpinning of humble lives. His mother took in laundry.

He identified with the people in the pages of P.Y. Gray’s story and divided his mural into four distinct frames created in sequence, left to right.

The first is a lament, a pastor presiding over mourners, children sitting idle on a fence before a string of tenant houses. The second image is reverent, figures with a handful of open books against a backdrop of children sitting, lining a wall.

In the third, women gathering a harvest and men working fields frame P.Y. Gray, his exaggerated hand open, sewing seeds over children singing before two students reading giant books.

Students in a hallway wave banners in a row of windows in the final frame. There’s a school bus wedging into the scene.

It was Kenzie Messer, this semester’s editor of Northeast’s student paper who researched and found the words Dr. Biggers said that day 28 years ago.

That same year Dr. Theisen began writing “Walls That Speak: The Murals of John Thomas Biggers,” the definitive work on the artist’s life.

With desegregation, Carver High had become Paul Pewitt Elementary School. The Biggers mural was taken down and stored for a while beneath the band hall, for a while in an outdoor shed, then brought back where it was first hung after the library was converted to a storage room.

In days when Northeast professors taught both credit and continuing education classes at off campus locations, Dr. Theisen was rummaging through the school storage room looking for a projector when she discovered the Biggers mural.

Dr. Biggers died in 2001.

The Paul Pewitt School district agreed to loan the mural for 20 years to Northeast. The college sent it to a Dallas artist and conservator for restoration. Before being brought to the campus, it’s got a 6-week stop at the Tyler Museum of Art.

“I’m absolutely over the moon that we will be able to show it here,” Tyler Museum Director Christopher Leahy said.