Bankhead Story for Connections

It’s a conspiracy.

The plan calls for every town on the line between Texarkana and El Paso to channel travelers down Mt. Pleasant’s main drag.

It’s the brain child of Dallas State Rep Carol Kent. It’s the result of the 2009 introduction of a measure designating a century-old route across Texas as part of a state Historical Roads and Highways Program.

Time was, The Broadway of America stretched from sea to shining sea, the first paved highway connecting every town square along the 850-mile drive across Texas to the Pacific Coast at San Diego and the Atlantic within an easy drive from Washington.

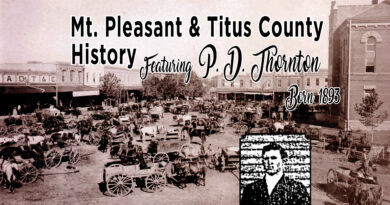

Long stretches of semi-sleepy U.S. 67 today follow the old road through East Texas from Texarkana to Sulphur Springs. A 1940’s shot of traffic along Mt. Pleasant’s Jefferson Street is featured in the opening fold of the first state brochure of Texas Historic Highways, Bankhead Highway, The Broadway of America.

“It’s about time,” said retired Professor Dale Truitt, organizer of the Antique American Independent Auto Association (AAIAA) April, 2016 four-day drive across Texas commemorating the 100th Anniversary of the President Woodrow Wilson’s 1916 signing of the “Federal Aid Road Act” written by Senator Hollis Bankhead.

The Bankhead Highway wasn’t a straight shot across America. Its dip from Washington into the Old South is directly linked to the Alabama residence of the enabling legislation’s author.

Its routes were fluid in early days, when towns competed to make the map. In those years the road split at Texarkana along rivaling ways, one generally following present U.S. 67, the other turning south and angling east to Hughes Springs, following present-day Texas 11 through Daingerfield and Pittsburg. It came together again at Sulphur Springs, according to the American Roads website.

“In terms of historic significance, the Bankhead’s bigger than Route 66,” said Professor Truitt, an American auto collector with membership in one of the nation’s more elite car clubs.

If the manufacturer of your American made car’s still in business, sorry.

Look for AAIAA purists behind the wheels of only original restorations of Pierce-Arrows, Packards, Grahams, Kaisers, Tuckers and Hudsons, or any of a host of American car manufacturers who’ve gone the way of the Studebaker.

Bankhead historian Dan Smith’s book, Texas Highway 1, The Bankhead, describes a turn-of-the 20th century “Good Roads” movement that led to federal funding of a national highway system.

“It’s a forgotten story, but the stuff every Texas school kid should know,” said Professor Truitt, a retired industrial arts instructor at A&M Commerce. “The Bankhead embodies what everyone should understand about the relationship between roads and economic development.”

The first phase of the Texas Historic Commission (THC) work was a two-year study identifying 2,700 historic “cultural resources” ranging from architectural styles of motels and gas stations that were the direct result of the highway to secondary impacts including the rise of billboards. As reflected by THC designated resources along the way, the road leads through a visual story spanning 50 years pre-dating the rise of the nation’s interstate system.

“The Bull Durham tobacco sign on the south side of Mt. Pleasant’s 1894 Caldwell-Carr building was part of America’s first outdoor advertising campaign,” Professor Truitt said.

Beginning in the last decades of the 19th century, Bull Durham commissioned New York artist Ruben Rink to use his art to advance the brand. He hired four crews of painters known as “Wall Dogs.” For 40 years they traveled America looking for buildings along high traffic routes as easels for larger-than-life depictions of the company logo. The south face of the Caldwell-Carr building towered over a livery stable and passenger trains rolling into the Cotton Belt depot on its east side and the courthouse square to the west.

Increasingly referred to by cultural historians as “ghost signs,” the artwork on the building where baristas now serve downtown’s first freshly-ground, hand crafted coffees at Jo’s proved up the value of outdoor advertising.

Billboards along roadways followed.

The new idea along the Bankhead is bigger than the individual tourism assets of towns along the route, said Donna McFarland, organizer of the first state-sanctioned Bankhead Film Festival last summer at Mt. Vernon.

“The bigger idea is the collective draw of all the assets in every town along the route that make it a destination for historic tourism,” said Mrs. McFarland, current President of the Mt. Vernon Chamber.

Along with Weatherford and Big Spring, the THC selected Mt. Vernon as one of three pilot cities working the Bankhead Project with Patrick McMillan and Associates, a San Antonio consulting firm.

The key to the marketing initiative is branding the Bankhead Highway name into towns along the route so that all are promoting a common tourism theme, Mrs. McFarland said.

“It can be anything,” Mr. McMillan said. “If you’ve got a community bingo game, make it Bingo on the Bankhead. If there’s already an established destination that’s ten miles off the route, instead of a ribbon of highway, include it as a draw along a broader Bankhead corridor.”

The Bankhead refined Texas government.

“When the funding act passed, one of the requirements for getting federal money was having a state highway department,” Professor Truitt said.

Austin got the message and in 1917 created the Texas Highway Department (now TxDOT) with a mandate to “get the farmers out of the mud.”

Titus County routes reaching back to the days of wagon roads became a part of a state route designated as Texas 1 that became a designated leg of the Bankhead after a military surveying convoy worked its way across Texas in 1919.

Coming west after crossing the town square at Mt. Vernon, the route passed through Winfield bending south into Farmer’s Academy following what’s now Farm Road 899. Merging into modern-day Ferguson Road at Mt. Pleasant, the route veers onto West 1st at O’Tyson, coming east along the south side of the courthouse. Turning north on Jefferson, the original route ran to 16th, turned east and followed what’s now a back road from town out to U.S. 67 east.