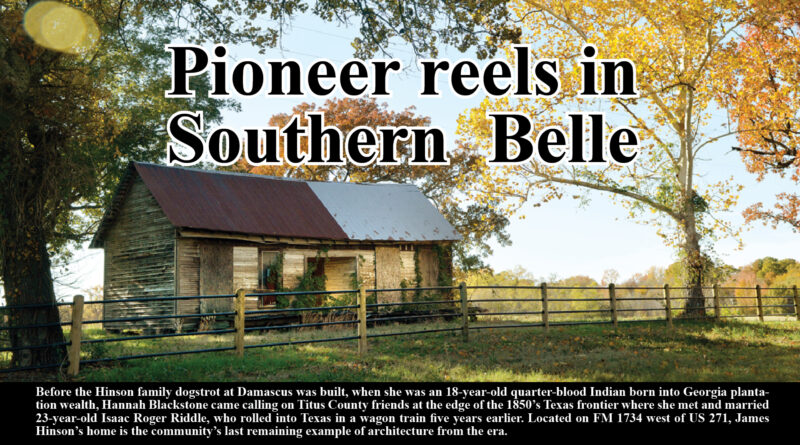

Pioneer reels in Southern Belle

By Hudson Old

Journal Publisher

As if her birth affected the cosmos, stars poured like rain from the sky the night Hannah Longstreet Blackstone was born. Leaving his wife to go for the doctor, Isaac Blackstone’s horse ran away with him as “fireballs” exploded in the heavens. “Earth Grazers,” as astronomers would later call those meteors that streak across the horizon leaving long tails of colored light, ignited the world “bright as day,” he later told Amanda, Hannah’s mother.

As her grandson told in the family story he compiled in 1968, November 13, 1833 came to be known as “The Night the Stars Fell.”

NASA Science Solar System Exploration’s description of the night both Hannah and the term “Meteor Shower” were born says that as many as 100,000 meteors an hour burned out in the skies across Georgia as Amanda Blackstone labored to deliver Hannah without the doctor who came too late.

In 1851, Hannah came to Texas to visit friends who’d come west and settled where land was either cheap or for the taking. Settlers began streaming into Titus County after The Republic of Texas joined the union in 1845. The way Fred Plum tells the story, it seems Hannah did not wait for the family to gather, nor did she return to Georgia with the future husband she unexpectedly met.

On December 18, scarcely more than a month after her 18th birthday, she married a pioneer who shared her father’s given name. Isaac Roger Riddle was “a poor boy from Boone County, Kentucky,” wrote Mr. Plum.

In that moment, she stepped into the pages of an American epic, a family history Mr. Plum compiled from family stories, land records, census data and a land grant awarded Dr. James R. Riddle for his service in the Revolutionary War. The Riddles were Scotsmen, Mr. Plum said, who’d come to the New World via England.

During the war for American independence, Dr. Riddle’s brother, William Thomas Riddle, was taken prisoner and hanged by the British for treason. A generation later, the Revolutionary War veteran’s fourth son Isaac left Virginia for Texas.

It was that Isaac’s youngest son, Isaac Roger Riddle, who caught Hannah’s eye.

“I don’t know how Great-Grandpa Blackstone took his daughter’s marriage into the family,” wrote Mr. Plum. The Blackstones were people of wealth and though Indian blood ran in Hannah’s veins, she was reared in the genteel traditions of the belles of the plantation South, he said.

Here, her life took a different turn.

After she came to Texas, fate served her tragedy upon tragedy.

Her father and four of her five brothers were killed in the American Civil War and buried in lost graves. Her fifth brother, William Luther Blackstone, came home from the war “shot through, with seven bullet holes in his body.”

Their fortune lost, her brother sent word that he had opportunity to sell their Georgia home and land. Cash starved after four years of war, “they sold the family plantation for two trunks full of Confederate money.”

Within months, the money was worthless.

Hannah, it was said, never wholly recovered from the death of her fourth child. An infant son, Joseph fell from his bed so that his head lodged between his bed and a log in the wall. Strangling, he made no sound as he died sometime in the night of July 2, 1859.

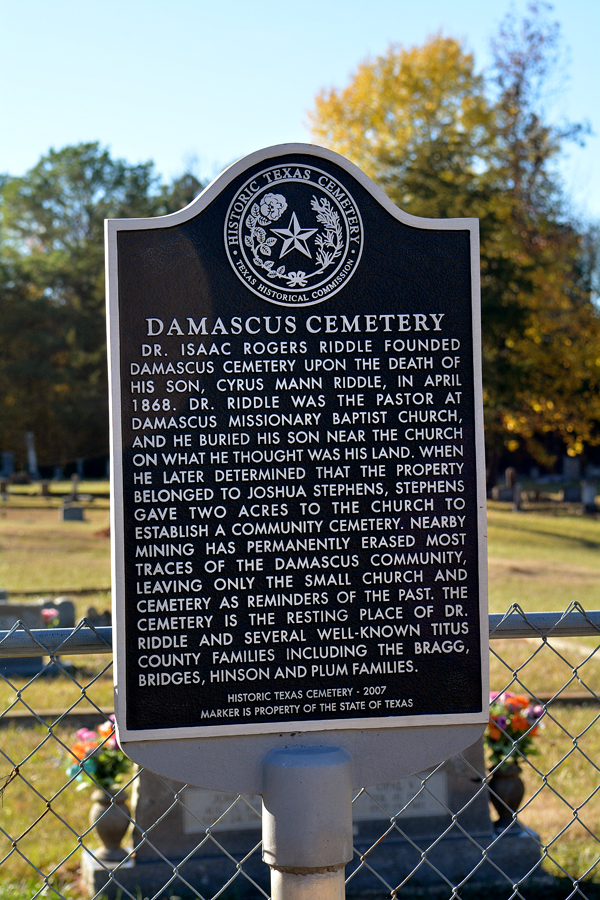

April 8, 1868, her second son, Cyrus Mann Riddle, was 14 when he died and was the first to be buried in the cemetery by Damascus Church where both his father and then his brother were Baptist preachers.

The remaining 10 of the 12 children of Isaac and Hannah Riddle survived to adulthood, growing up in the community that came to be called Damascus, the name Isaac Riddle gave the church he pastored near the road that became the Paris to Mt. Pleasant stage coach route.

A pioneering settler, over the course of his life in Titus County, Isaac Roger Riddle was a farmer, a pastor, a wagon builder, a politician and a physician.

He became the Reverend Doctor Isaac “Ike” Rogers Riddle after applying for and receiving a medical license from the state in 1855.

After selling out in Georgia, William Blackstone joined Hannah and her extended family in Texas where he married Huldah Saunders in 1868. They had 12 years together before William died of old war wounds in 1880, wrote Mr. Plum. Huldah died of pneumonia two weeks later, leaving three orphaned children.

In the social order of the day, there was always more room in a home. Dr. and Mrs. Riddle blended two nephews and a niece into their group of ten surviving children.

All were grown when Hannah died in the summer of 1896.

She was buried the next day at Damascus.

“My mother, Jennie Riddle-Plum, did not get to go to the funeral because she was in Cass County and knew nothing of it until three days after Hannah’s burial,” said Mr. Plum. “This broke my mother’s heart.”

Fred Plum did well keeping his Isaacs straight in the story of that branch of the Virginia Riddles who became Texans. There was Hannah’s father Isaac, her husband Isaac, and her father-in-law Issac, a hatter by profession and an adventuring pioneer at heart.

Father Isaac was born in 1777, before his father’s service concerning the matter of American Independence from England was satisfactorily settled. In May of 1801, when he was 24, “he went over the mountain into Tennessee and married Anna Grizzel, says the Riddle family story Mr. Plum compiled. The couple moved twice before settling in Boone County, Kentucky on a creek called Riddle’s Run.

All of their 11 children were born and were married in Kentucky except for the last son, Isaac Roger Reynolds, who was 19 in 1847 when his 70-year-old father decided the family should move west to Texas. His mother was 63.

Titus County was the edge of the frontier when they got here late in the winter of that year. They were among as many as 19 family names setting up their last camp at Red Springs, which now is Dellwood Park.

The journey began when father Isaac and his sons built flat boats, “loaded their possessions and floated down Gun Powder Creek to the Ohio River, down the Ohio to the Mississippi, riding the river as far south as the mouth of the Red River in Louisiana,” says Mr. Plum’s story. “Then they poled laboriously up the Red River to Shreveport where they unloaded their boats and formed a wagon train headed for Texas.

Mr. Plum had no records concerning the people in the wagon train, but recorded names remembered in Riddle family stories passed down for two generations before he began writing.

Single men and families that joined the caravan included Alexander Nevils, Samuel Morris, A.C. Smith and C.H. Lennon. There was J.W.G. Wood, William Batte and his son, Dick; a man named Reynolds and brothers T.S. and T.J. Rogers.

There was Samuel Cochran, whose name was also spelled and pronounced Cawhorn. Others included: W.J. Williams, William Keith, L. Ainsworth, William Simpson and a wagon maker named William Mann Stephenson.

Places they came from included Alabama, Georgia, Tennessee and Kentucky.

“Up into the Piney Woods they came, along the southwest shore of Caddo Lake into Texas near what’s now Karnack,” Mr. Plum said. “They blazed a trail along of near what’s now the route of Highway 49.”

Initially, the oxen pulling the wagons covered eight to 12 miles a day. That changed with the weather and they holed up and sheltered in camps as best they might in rains that turned to sleet and snow as fall became winter.

“When bad weather came on that fall and winter, many of the people in the caravan got sick and lots of them died,” as the story goes. “Almost every campsite began a new cemetery. They’re all along the route from Jefferson to Mt. Pleasant. Their camps were forerunners to communities including Kellyville, Avinger and Hughes Springs.”

At Daingerfield, there was a post office that had opened a year before, in 1846.

Leaving Daingerfield, the next camp was named “Snow Hill” for the weather that overtook them just north of what’s now Cason. One of the sons of father Isaac, Elam Riddle, his wife Matilda and children stayed on for a while at Snow Hill, one of the earliest settlements after the new Texas state legislature created Titus County on December 13, 1846. Elam’s brother, James G. and his wife Lucy patented abstract 466, claiming land at Snow Hill where the cemetery called Blevins began.

Thomas Gregory Riddle, who married Nancy Morris back in Kentucky in 1832, settled at Union – now Old Union on U.S. 67, west of present-day Cookville. They’re buried in the part of the cemetery on the south side of the highway, across from the site of the old church.

Father Isaac Riddle, who’d come to Texas at 70, died at 84 on November 30, 1861. By then he’d been a widower almost five years. Anna died late in the winter of ’56.

Within months of his death, his son Doctor Isaac Reynolds set up a factory building “linch-pin” wagons for the Confederacy in the Forest Grove – Damascus community.

On October 11, 1868, six months after he and Hannah had buried their 14-year-old son near the church at Damascus, he was ordained as a Baptist Minister.

In 1878 he was elected Titus County Judge, served one term, got beat, came back and won a second term, then retired from politics.

After Hannah’s death in July of 1896, the nearly 70-year- old widower Reverend Doctor Riddle married the widow Nancy Milstead, a younger woman in her early 60’s.

“For a day or two this brought the wrath of his children down on them,” wrote Mr. Plum. “When he returned home from Goolsboro (now Talco) with his bride, they all met him at his home to tell him off. But it ended up with all the wives cooking them a big Riddle Dinner and they all accepted her as their second mother and she lived up to her part of the deal.”

On the ninth day of March, 1903, when he went out to his barn and didn’t return, whoever went looking found the Reverend Doctor deceased. He might have had a heart attack or he might have been kicked by a mule – having heard it both ways, Mr. Plum wrote it that way.

Born in the Forest Grove – Damascus Community on October 16, 1900, Melvin Bridges never knew Isaac, but he knew stories of him. In one of the better ones, it was said that “Dr. Ike preached many sermons in a log church at Damascus with his six shooter laying by his Bible in case the ‘toughs’ tried to break up the services, which they sometimes did,” Mr. Bridges said in an oral history project recorded in the 1970’s and donated to the Mt. Pleasant Library.

Former Titus County Commissioner Al Riddle, now retired and fishing the Alabama coastal bay a block away from his place on the Gulf, heard a similar family story about the Reverend Doctor bringing his gun to church.

“He was known for long sermons,” Al Riddle said, “and I was told he’d pull his pistol if anybody tried to leave before he was through preaching.”