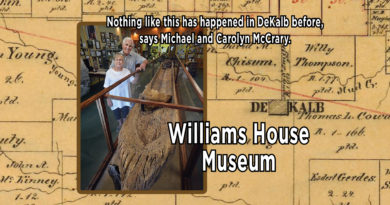

Titus County namesake statesman surfaces on Red River near DeKalb

DeKALB – Titus County namesake Andrew Jackson Titus surfaced amid news clippings and Republic of Texas records, a paper trail into East Texas at the Williams House Museum. Born in 1814 in Madison County Mississippi territory that today is the state of Alabama, A.J. “Jack” Titus was named for the hero of the Battle of New Orleans, where the English were driven off the gulf coast in the War of 1812.

The fourth son of James and Nancy, in 1832 Jack Titus first came to Texas with his father, who signed on to escort Indians moving west along the “Trail of Tears.” In 1830, President Andrew Jackson signed the Indian Removal Act driving Indians west.

Arriving on the heels of the Texas Revolution, in 1836 Jack Titus came to Texas to stay. Passing through Arkansas to a crossing on the Red River at the Mouth of Mill Creek, he got land 10 miles south of DeKalb.

“The stories from the Mouth of Mill Creek are Bowie County’s most well-kept secret,” said Williams House Museum’s docent for all seasons, Mike McCrary. A writer and researcher, Mr. McCrary’s work often follows the course of the Red River into the frontier.

In the pages of journals, he’s found Spanish soldiers confronting an American scientific expedition at Spanish Bluff, an escarpment maybe no more than a mile along the Red River from the Highway 8 bridge fifteen minutes from town.

“When Spain still held its claim to Texas, President Thomas Jefferson sent the Freeman and Custiss expedition up the Red River,” Mr. McCrary said. “This is as far upstream as they got before the Spaniards turned them back.”

From maritime records he found in New Orleans, Mr. McCrary has documented locations of ports upstream of Shreveport as far as Fannin County during the years of steamboats plying the Red.

The Mouth of Mill Creek was among the earliest, coming from the dawn of Anglo settlement there 200 years ago. With exceptions for passing French, Spanish and early American expeditions, it’s as old as the recorded history of the right corner of Texas gets.

“Virginia-born Charles Burkham built a home that began the first permanent Anglo settlement on the south bank of Mill Creek in 1820,” Mr. McCrary said. He was a frontiersman, a hunter, a planter, an Indian fighter who stayed to fight for independence in the war for independence from Mexico.

Before that, when Mexico still laid claim to Texas, settlers wanting title to Texas land filed questionable claims in Arkansas, depending on who drew the map.

“In 1829, the seat of justice of old Miller County, Arkansas was temporarily moved to the home of Charles Burkham on Mill Creek,” Mr. McCrary said.

In 1830, Mr. Burkham was elected sheriff of Miller County. He was murdered in 1837. The motive was robbery.

“He was searching for a runaway slave,” Mr. McCrary said. “His assailant mistook the chains and hand irons in his saddlebags for gold.”

The Stout family name in East Texas is first attached to Mill Creek, where Henry Stout was among the original settlers at Burkham Settlement. He wandered on from the river, ranging over the Texas prairies in 1829.

“Henry Stout led forays against hostile Indians,” Mr. McCrary said. “He was in the Village Creek Fight of 1841 near Fort Worth.”

In 1839, Captain W.B. Stout from Traylor Russell’s History of Titus County organized a company of 42 men to destroy a village on White Oak Creek that Stout described as a “rendezvous for Indian renagados.” Later that same year he commanded construction of Fort Sherman in southwestern Titus County where the Cherokee Trace crossed Big Cypress Creek.

By the 1850’s, trails from the east funneled Texas immigrants through Burkham’s Settlement.

When the newspaper at Sherman reported a train of 125 wagons passing through town, Charles Demorse responded in Clarksville’s Northern Standard.

“We have a similar report,” he wrote. “This morning, about 100 wagons from Kentucky and Tennessee came through town.” He said wagons coming west crossed the river at Mill Creek.

“Rivers of the United states served as highways of development,” Judy Watson said in her story, “The Red River Raft,” written for the East Texas Historical Journal in October, 1967.

Transportation was the issue that made Jack Titus a household name in Mt. Pleasant. He’s credited with opening the road through Mt. Pleasant connecting the Port of Jefferson on Big Cypress to ports on the Red River north of Clarksville.

During his brief service to the Republic of Texas Congress, Jack’s father James had made Texas statehood and transportation his defining issues.

“Just before his death he wrote to his friend and political ally General Sam Houston,” says the family narrative compiled by O. Lynn Titus. He wrote urging Houston to call for the Republic Congress to build toll bridges over the Sulphur and both branches of the Cypress River and to develop a road between Clarksville and the old Spanish settlement at Nacogdoches.”

“Meeting of the Raft Convention,” reads a headline from the December 11, 1847 Northern Standard at Clarksville. The raft was a series of log jams hindering riverboat trade on the Red River. Depending on the source, the length of the Raft was said to have been between 60 and 100 miles.

“Navigation was never entirely impossible, for there were always routes around the barrier through bayous and lakes which lay on either side of the river valley,” Judy Watson wrote.

Two years after becoming America’s 28th state in 1845, representatives from Texas, Arkansas and Louisiana called for the convention at Clarksville to draft a resolution to the U.S. Congress to clear the channel of the Red River.

“Federal troops protecting the frontier are stationed above the Raft and the only channel for their securing supplies is Red River,” the resolution said.

The resolution warned of the potential for conflict with Mexico, still stinging from defeat in the Texas Revolution. It said Mexico could exert influence on “various tribes of people who reside in countless numbers immediately at and around the frontiers of Texas” and that defense of the nation’s border demanded free flow of troops, supplies and “munitions of War.”

In 1843, when Red River County’s patriarchs were working to raise $450 in “subscriptions” for defense against “Indian depredations,” The Northern Standard reported in its June 15 edition that Jack Titus was “willing to buy horses and arms upon the faith of it, and furnish those who are themselves unable to fit out. The amounts subscribed are to be paid to him in cotton or land on the first of January next.”

The image of Jack Titus first seeing Texas from the Trail of Tears filters up from aristocratic roots of the family line. When Alabama territory was carved out of the Mississippi territory, his father James was one of three men seated on the territorial legislative council proposing statehood. The first died before the council convened. The second resigned, leaving James Titus as the sole member.

“According to records of the first session of the assembly, Titus elected himself President of the Senate, chairman and member of each committee, and ran the upper house as a one-man enterprise,” as reported by the account of his great great grandson, O. Lynn Titus.

From Mills Creek, Jack Titus next appears in the earliest pages of DeKalb’s story. In 1838 he was one of 26 petitioners calling on the congress and senate of the Republic of Texas to establish a “college.”

The petition recommends him as a trustee.

Given the common story of communities with “colleges,” Mr. McCrary reasons that the term might have been used to describe a community school rather than a school for secondary education.

James Titus was appointed to the Republic legislature in 1842, a year before he died.

He replaced Robert Potter, a rake and a rambler, a ladies man who’d fled prosecution for emasculating a man he’d accused of being his first wife’s lover. Arriving by ship as a Mexican military advance from its victory at the Alamo turned into the Texas revolution’s Runaway Scrape, Potter steps into an epic tale chronicled in Elithe Hamilton Kirkland’s historical novel, Love is a Wild Assault. He was shot and killed at Potter’s Point on Caddo Lake by William Pickney Rose during a “local” war between the “Moderators” and the “Regulators.”

After his father’s death in 1843, Jack Titus “sought the annexation of Texas, a task requiring him to spend much time in both Austin and Washington,” Mr. McCrary wrote in one of a series of papers, “Sights and Sounds from My Swing.”

He surmises that the son might have been continuing the work of his father who’d replaced Potter in the legislature.

Jack Titus was a sporting man.

“In August, 1847, his horse Alice Grey was to be pitted against J.K. Oliver’s horse, Georgian, at the sweepstakes races at the track in Clarksville,” says the “Sights and Sounds from My Swing.”

In 1851, Jack Titus advertised a 5-year-old Thoroughbred Stallion, Hector, a mahogany bay with black legs mane and tail as “standing at stud during the season.”

Time was, Clarksville emerged as the town of record, the town with the newspaper that promoted not only its town, but its region. The Titus family committed to nurturing commerce becoming the economic backbone of an emerging state naturally gravitated to Red River County.

Jack Titus, Royal Arch Mason, Knight Templar and public servant died at his residence in the Red River County community of Savannah on April 9, 1855.

The Williams House Museum and Mr. McCrary’s Texas research have been featured on National Public Radio’s “All Things Considered.”