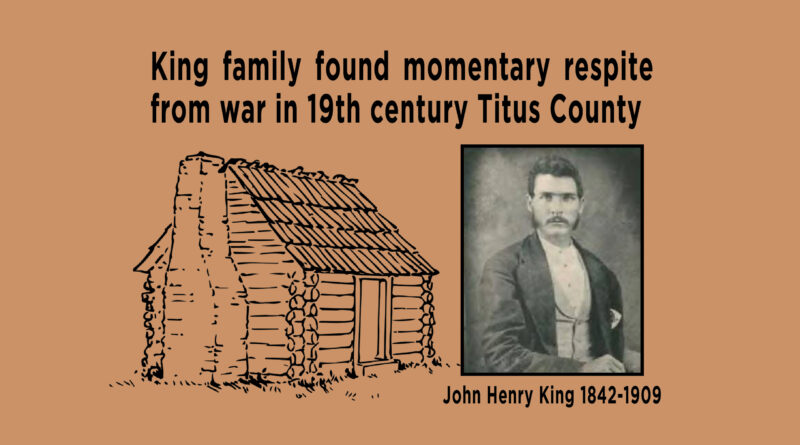

King family found momentary respite from war in 19th century Titus County

John Henry King remembered the soldiers passing by his home at Boggy Creek in eastern Titus County on their way to the war in Mexico.

“During the summer of 1846, two U.S. Regiments of Cavalry passed our new home,” he wrote. “One was from Kentucky, the other from Tennessee. My mother and father had many friends and kindred among the troops.”

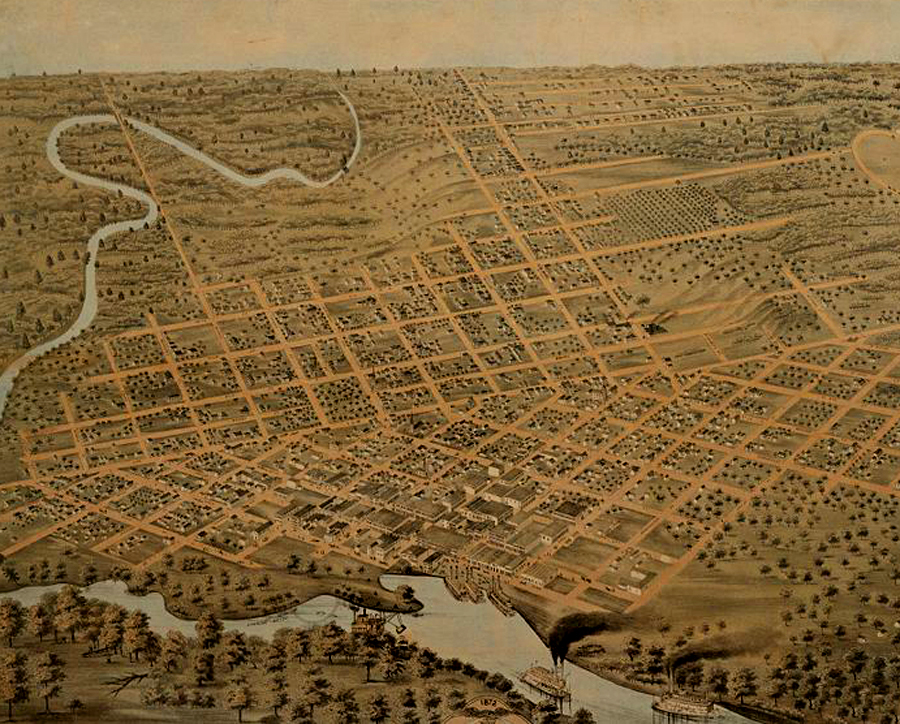

His family came from Tennessee, arriving at Jefferson late in the spring of 1846. Born about 1842 according to military records from the Confederate States of America, when he sat down to write of his life some 60 years later, Captain King recalled details about his family’s move to Texas.

“Within a few days of our arrival at Jefferson, Mike Barrier moved us to Boggy Creek in an ox wagon,” he said. “Spring was far advanced. The road on either side of us was strewn with wild strawberries.”

He dated his memoir July 23, 1906, three weeks to the day after the death of his wife, a reflective time.

His father, Carter Beverly King, fought in the Creek and Seminole Indian Wars (1830s). His grandfather, Henry King, fought in the war of 1812. His great grandfather, Harry King, came from England with an Irish bride named Betty Brown.

“Harry fought from beginning to end in the American Revolution,” Captain King wrote.

He made a one-line mention of his own military service. A cousin, William Sergeant King, “was killed by my side in the Battle of Murfreesboro (Tennessee) on December 31, 1862.”

His wrote instead of his grandfather’s stories of fighting alongside Davy Crockett and Sam Houston in the Creek and Seminole Indian Wars.

In 1851, Henry King joined other members of the King family in Titus County. By then, the Kings had moved to a cabin on Horse Creek, also east of Mt. Pleasant, “about two miles from the present-day site of Cookville.”

His mother’s side of the family came as well. Like the King family, they’d lived through violent times.

“My great grandfather and great grandmother, James A. Ferguson and wife, were murdered by Tories in South Carolina during the war of the revolution.” A surviving son, also named James A. Ferguson, was a wagon master in the war of 1812.

In Titus County, the family found a brief respite from war.

They prospered early. “The year 1847 was a fine crop year; a bale of cotton per acre, price 6 cents per pound,” he wrote. “There was a good deal of sickness. My uncle Pleasant Miller Ferguson, my brother Pleasant Miller King and our neighbor, Rev. John B. Cherry all died that summer.

“The Mexican War was at its height under General (Zachary) Taylor in northern Mexico and my father wanted to go to it, but we were a young and helpless family among strangers and on unimproved land and he couldn’t volunteer.” In 1848, Carter Beverly King finished building the family’s new home on Horse Creek.

“Pardon me for giving a faint description of our home, but in 1848, the face of nature was a poem to me. The primitive woods, the high green grass, the ferns and wildflowers in profusion intoxicated my being and have left me with visions and perfumes that I’ve still not forgotten. There is nothing on earth like it now, like our neat little cabin, one room and a loft of plank, and sheds on both sides. There was a smoke house, and we planted a small peach orchard. We had four acres in cultivation, a crib and a stable, a walled spring within 30 yards and a creek within 50 yards. Green cane lined the creek bottom to the foot of the hills — not switch cane, but big cane, big enough for fishing poles. The creek was deep, blue and clear, and running all the time; full of fish and in shallow places could be seen shoals of mussels by the hundred. The woods were alive with snakes, all kinds and sizes. There was a ridge of pine timber a few hundred yards south, tall and stately I thought. In winter, in cold weather, or after a rain, those pines would loom up so lively and green that I watched them for hours.

“There were eleven families with a school house and a church house, some of the neighbors as close as a half mile. The names of the families were as follows: J.B. Keith and D Young, Warren C. Keith, William Keith, Jo Keith, J.H. Keith, William Tigert, William Heath, William (Buck) Taylor, James Spencer and John Rogers.

“We had school all the time and preaching occasionally. In the spring and summer the soldiers came back through, returning from the Mexican War. Deer frequently came within gunshot range of the house and were killed from the door. We had a few cattle, horses and hogs on the range.

“Our teacher’s name was Boris Cantrell, from Tennessee. In 1849, his brother, Pickney, moved to California, traveling overland to the gold diggings. Many of our friends and acquaintances went to California to dig for gold, and many of them perished for water crossing the deserts. Some fell sick and died; some were killed by Indians.

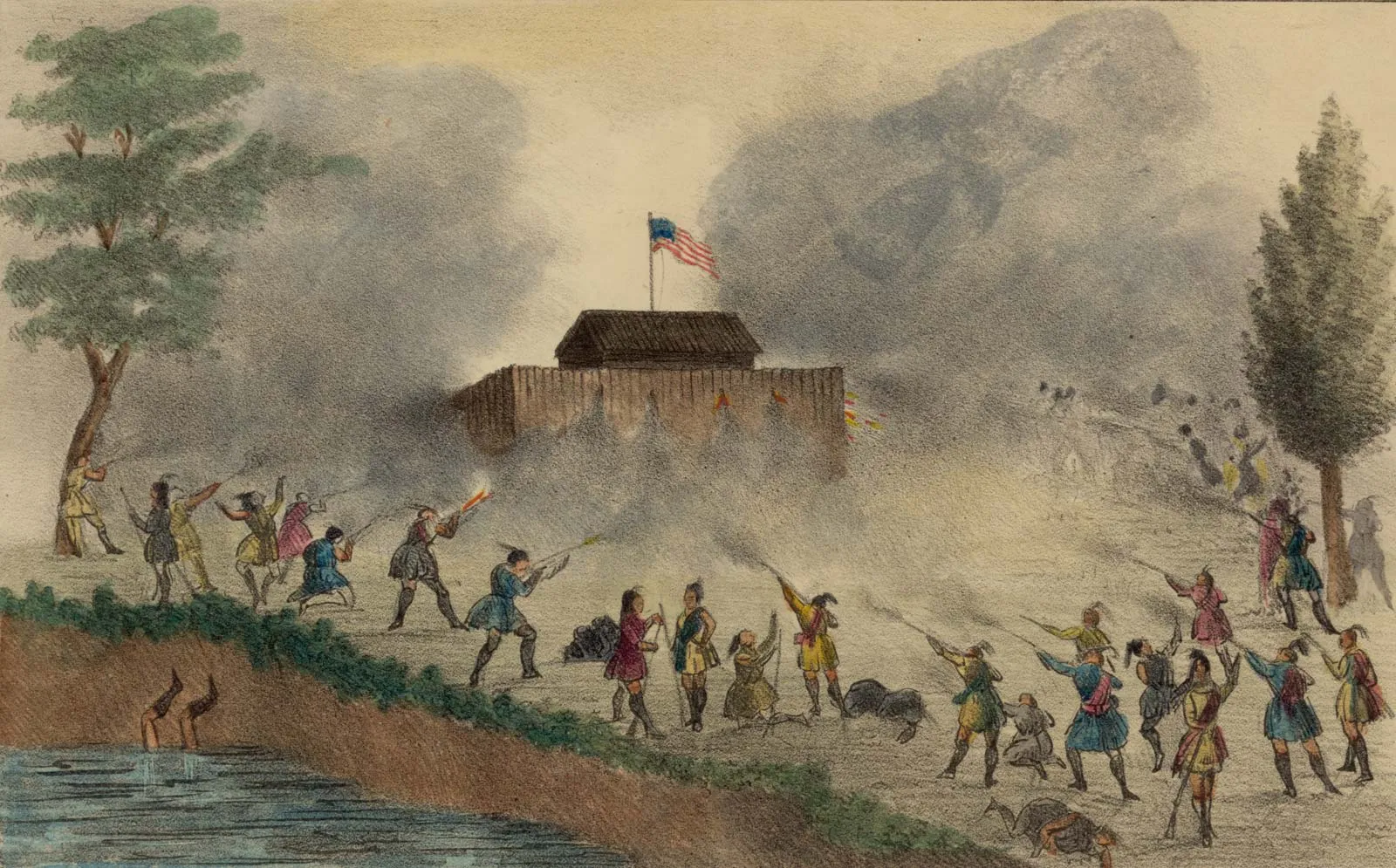

“In the fall of the year Indians passed our house one day and set the dry grass afire all over the country. They were on horses. The next morning the families forted up and 40 men rode after the Indians. Five years before, Indians had murdered the Ambrose Ripley family west of Mt. Pleasant.

“When my father and the company overtook the Indians they refused to talk, only grunted. The white company prepared to fire on them, and then the old Chief talked and said they were friendly and had a permit to hunt and were ring firing to kill deer. They were told they must get out of the white settlements and stay out, which they promised to do and did so. For several years afterward, we would come across signs of Indians, but no bands traveling through the country.”

He remembered hard times. “We had a genuine blizzard a day or so before Christmas, 1854. There was an eclipse of the sun the following June and it quit raining and rained no more until November, and then only sprinkled a few days.The fires got out in the fall and like to have burned all the range out. Dead trees burned down into the roots and the grass and turf burned down beneath the surface of the ground.

“The canebrake in the bottoms got afire and burned for weeks during the fall and winter. Horses and cattle would go down into the creeks to hunt for water and starved for want of it.

“Navigation ceased on the Cypress River at Jefferson, then it ceased on the Red River at Shreveport, our next closest market and we had to go to Alexandria, Louisiana for our groceries. The Red River soon got dry there and we had to go for groceries and dry goods by ox wagons 350 miles to Gaines’ Landing on the Mississippi River. Salt was $12 per sack.”

According to records from the Confederate Army, John Henry King, 19, joined the 9th Texas Infantry in October, 1861, enlisting at Daingerfield.

In his “History of the 9th Texas Infantry,” Tim Bell writes that measles and pneumonia broke out shortly after the regiment’s organization while they were camped in Lamar County.

In March, they arrived at Corinth, Mississippi. During the month, the regiment lost an average of two men a day to disease.

“The regiment was armed with a variety of small arms, including double barreled shotguns, sportsman’s rifles and muskets, many of them in bad order. Sick, poorly drilled and without reliable weapons, the 9th Texas was about to face the dreaded foe for the first time,” wrote Mr. Bell.

On March 26, the 9th Texas joined J. Patton Anderson’s brigade, Ruggles’ Division, Bragg’s II Corps at Shiloh.

“On the morning of (April) the 6th we advanced in line of battle under heavy fire of artillery and musketry from the enemy’s first encampment. Being ordered to charge the battery with our bayonets, we made two successive attempts; but finding, as well as our comrades in arms on our right and left, it almost impossible to withstand the heavy fire directed at our ranks, we were compelled to withdraw for a short time with considerable loss,” wrote Colonel Wright A. Stanley.

The Confederates called for artillery and charged again, “routing the enemy from their first encampment and passing through two other lines where we found our troops again heavily engaged to the galling fire of a second battery and its supports, to which my regiment was openly exposed.”

The 9th stubbornly charged. Stanley’s horse was shot from beneath him, but his men drove the Union soldiers from their battery to win the day.

That night, the Union army brought up reinforcements and on the morning of the 7th the battle began again, with the Union soldiers driving the Confederate lines back to “basically the same positions that Grant’s army held on the morning of the 6th,” Bell wrote. Of the 226 men of the Texas 9th Infantry, 14 had been killed, 42 wounded and 11 were missing.

Through the spring and summer, the Texas 9th remained at “Camp Texas” near Tupelo, Mississippi. Providing ordinance for the regiment’s hodge-podge of weapons had been a nightmare, but in September they received 360 Belgian rifles.

In October they joined Cheathams’ Tennessee Division in time for the battle of Perryville where 15,000 Confederates faced the larger part of the Union army.

In December the 9th joined five regiments of Tennessee infantry, Allin’s Sharpshooters and Scott’s Tennessee Battery. December 31, 1962, the day Captain King saw his cousin killed, was the same day he lost his arm in battle, and went down as the bloodiest day in the regiment’s history.

Braxton Bragg’s Army of Tennessee, with the Texans attached, attacked Union Major General William S. Rosecrans Army of the Cumberland near Murfreesboro that day.

“In hard fighting, Bragg’s men drove the Union army several miles before being halted,” Bell wrote, but for the Texas 9th, the price was staggering.

“Fighting almost alone and surrounded, the 9th became separated from the other regiments in the army. Finding his regiment penned down by artillery fire, and having lost 100 of his men in a matter of minutes, Col. William Hugh Young unsheathed his sword, brandished the regimental colors and called for an attack, driving the blue-clad attackers from their positions,” Bell wrote.

Of the 323 officers and men going into battle, 18 were listed as killed, 102 wounded and two captured or missing.

Writing of the battle, Quartermaster Thomas H. Skidmore recalled General Cheatham ordering Lt. Col. Miles A. Dillard to charge an artillery battery after Young was shot and Dillard took command. Dillard said his regiment didn’t have a cartridge left. General Cheatham ordered them to charge with bayonets, Skidmore wrote.

The one-armed Captain King returned to Titus County. In 1866, the year after the Confederate surrender, the uncle whose son was killed by his side was elected to another term as county treasurer before being removed from office by federal troops during the 10-year military occupation of the South.

On January 4, 1871, Captain King married Mattie J. Ward in Titus County. No longer suited to life as a farmer, Captain King began practicing law and was elected county attorney. He and Mattie had three children: Henry C, Mary C. Cross (wife of R.K. Cross) and “Miss Birdie,” he wrote.

He buried his wife at Cumby and his memoir was transcribed by Carolyn Cross Ireland, a granddaughter, who added notes about his term in office and the loss of his arm along with this note: “his remains were followed to their last resting place (Cumby) by a squad of Confederate veterans.”