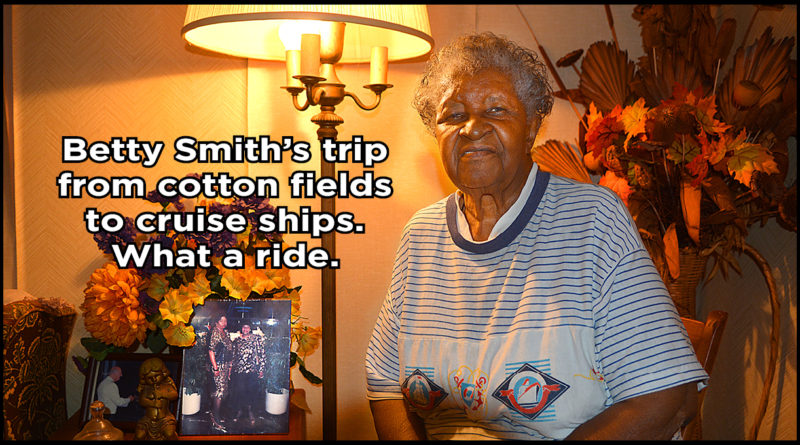

West Side woman’s got it figured out

By HUDSON OLD

Journal Publisher

Time was, Betty Smith worked in cotton fields to make money for school clothes. Jerry Walker said he’s heard stories of heat rising so thick from cotton fields you could see it shimmering in the air, like germs.

Today, Betty Smith tends a flowering garden of potted plants by her porch swing. Most of a lifetime’s passed since she dreamed of new dresses on the wind-whipped, back-of-the truck ride to field-hand living quarters with an outhouse.

That was in Hunt County, outside Greenville.

Seventy-odd years later, between the couch and the living room corner with her rocking chair, a lamp on the end table lights her souvenir shot from a cruise liner gliding through the Caribbean. It’s framed beneath an artificial arrangement of blue and gold flowers, the Booker T. Washington school colors.

One time, she was Most Popular Girl, as noted in the school yearbook, The Washingtonian. She was a twirler. She ran track and there’s a dwindling remnant still remembering her prowess on the basketball court.

She graduated in 1955.

Booker T. Washington closed in 1968.

She serves on the school bi-annual reunion committee. It was cancelled this year.

The reunion, not the committee.

Committee membership is lifetime, like a Supreme Court appointment.

“Pulling” cotton means pulling the whole bowl off the plant.

“Picking” cotton means picking the cotton out of the bowl. They stuffed cotton into long burlap bags pulled along behind, dragging the ground as they filled.

“Mmm-hmm,” she hummed a musical two-note prefix to memory of a sister who “could pick circles around me.” What was aggravating then makes her smile now.

There’s also “chopping” cotton.

That’s cultivating rows stretching from daylight to dark with a hoe. On Saturday, Lorenzo Baker’s truck took everybody to town. She shopped Greenville merchants’ store windows and made payments.

“We put our school clothes on lay away,” Betty said.

That was sometime after her father died in 1944, after they’d left Daingerfield for Dallas, where they lived a time with relatives before coming to Mt. Pleasant. In Dallas, her mother, Mary Younger, found work as a school cook. In Mt. Pleasant, she worked as a maid.

Betty helped. She learned to run a floor buffer cleaning Dr. Fender’s clinic.

Her mother worked for George and Lucille Stinson. Mary Younger is buried at Forest Lawn, beside Mrs. Stinson, whose daughter gave her the plot.

“When Mrs. Stinson passed, my mother was holding her hand,” Betty said.

Summer afternoon shade under the canopy of the oak at the edge of the lawn covers everything from her house to the street, a deep shade where lush green moss covers the ground around the tree trunk.

The lawn’s swept.

Where she’s got sun, there are flower beds built of native stone.

The intersection of MLK and Pecan Street is a tidy place. Everybody keeps their lawn, all four corners. Looking west up Pecan, there’s the back side of the Pilgrim’s Pride Poultry plant that for a time when Betty Smith was there is said to have grown into the biggest poultry processing plant in Texas, maybe America.

Looking east, the street’s framed by trees and passes Oaklawn Park on its way out to South Jefferson. For fun, on Saturdays, Betty Smith was a starter on Maurine Fields’s women’s softball teams.

They played teams from Pittsburg, Daingerfield and Cason. Joe Traylor’s boy’s teams started practice in the park on Saturday mornings. By the time the girls got to Oaklawn Park, there was a crowd.

Tribes of lizards dwell in her flowering front-porch potted plant garden. They are regularly watered. They thrive on a bug buffet. They lounge in lush leaves.

Defending her home against a green one that likes coming in, Betty Smith wedges a rolled towel under the screen door with her walking cane.

Arthritis.

“Arthur,” she calls it, a nagging companion.

It’s not an uncommon condition for poultry processing retirees, said Mt. Pleasant City Councilman Jerry Walker.

“Twenty years of standing on concrete working the processing line?” he said, posing the fact of the matter as a rhetorical question, assuming wear on bones as a given connected to eight-hour shifts of repetitive tasks.

Councilman Walker was the liaison connecting me to Betty Smith’s dining room table on her 86th birthday. Arthritis bubbled up in the conversation when it took eight rings for her – and not without a honed efficiency of movement – to unscrew herself from her chair and step around the corner to the phone in the kitchen.

The first birthday wishes call came from her granddaughter.

The second was from her sister. By then, our relationship had changed.

“Answer that, would you?” she invited. She told her sister “the newspaper” was there to do a story about her.

“From picking cotton right on up,” she said, which was the funniest thing either of them had heard all day.

Councilman Walker’s insight concerned the ways the poultry plant changed the world before that first call put arthritis on the table.

In turn for years of shift upon shift tending a production-line river feeding live chickens in one end and turning grocery-ready fryers out the other, came “the first chance for everybody to make a wage above working poverty,” he said.

Not that there weren’t success stories in the West Side’s Black Business District. There were successful tradesmen — electricians, plumbers and carpenters.

Pilgrim’s facility wasn’t just big. For women in particular, entry-level wages provided a living wage. A modest one, but a real one, Councilman Walker argues.

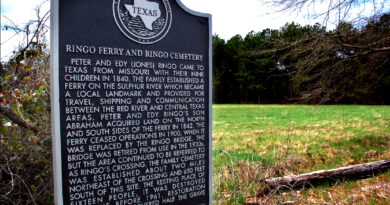

It was close enough for West Side residents to walk to work. They wore short-cut trails through Cortznes Cemetery.

(Last spring, incoming Councilman Walker got unanimous council backing for cleaning, fencing and following deed trails to establish lost corners of Cortznes Cemetery, which is actually a merging of various church, community and family burial grounds, some of the oldest in Mt. Pleasant, Councilman Walker said.)

Seven years out of school, Betty Smith traded the comfortable uniform of domestic work for chicken plant rubber boots and a rubber apron to turn water. She wielded a black-handled butcher knife, cutting necks of mostly washed plucked and gutted birds dripping along the line.

“I remember those knives,” Councilman Walker said.

Betty could carve the heart, liver and gizzard from an eviscerated carcass gliding by at production-line speed before it was out of reach. They say if she stepped away from the line, it took two people stepping in to keep the pace.

The line ran faster over the years, as they added automation. On Wednesdays, working first shift gave her time to go home, unwind an hour and change clothes before going to open up the church.

“She was always in charge of the children’s activities,” Councilman Walker said.

She was there early in the plant’s story, just after Bo Pilgrim cut a deal buying into a struggling (read as hired-gun management going down) vision underwritten by an assortment of chamber and business community bankrollers personally on the note* for a processing facility to anchor development of a poultry industry for a family-farm region. (*This was before the 1990’s beginning of sales-tax funded economic development. Bo Pilgrim signed on with the Mt. Pleasant backers, buying them out over time.)

Betty Smith retired in 2004.

She’s got a key to the Cottrell Chapel church. She opens up. She goes up early to turn on the heat or the air, as needed.

In April, they waved off her duty on the Booker T. Washington Bi-Annual Reunion Committee. The whole weekend fell apart. The parade was cancelled. Pandemic meltdown took out the Friday night mixer and the Saturday dinner dance. The Distinguished Alumni committee never met.

It was set for June 19. The parade was to have wound up in Oaklawn Park for the ceremony and speakers and revealing of the marker honoring Joe Traylor.

Saturday, William “Willie” Williams was to have been the keynote speaker for a ceremony at which the Distinguished Alumni Committee would have announced its selection for 2020.

A citizen coming of age in another era, Coach Williams came from Camp County, taught at Booker T., and transitioned with desegregation in 1969 to the Mt. Pleasant school district. He was elected to the Titus Regional Medical Center board. He retired as a school principal.

He died May 10.

They cancelled everything else, but they had the ceremony dedicating the marker anyway, which came to Betty Smith’s mind as she found a picture of him from his student days in the 1950 Booker T. Washington Washingtonian Yearbook Councilman Walker brought along when he called on her birthday.

“Here’s Joe Traylor,” she said, slipping into a story Councilman Walker interrupted.

“He passed this morning,” Jerry Walker said, and the conversation paused for a slow three count.

“Mmm-hmmm,” Betty Smith made a musical two-note melody. And on a not unpleasant note, “He’s calling The Roll,” she added.