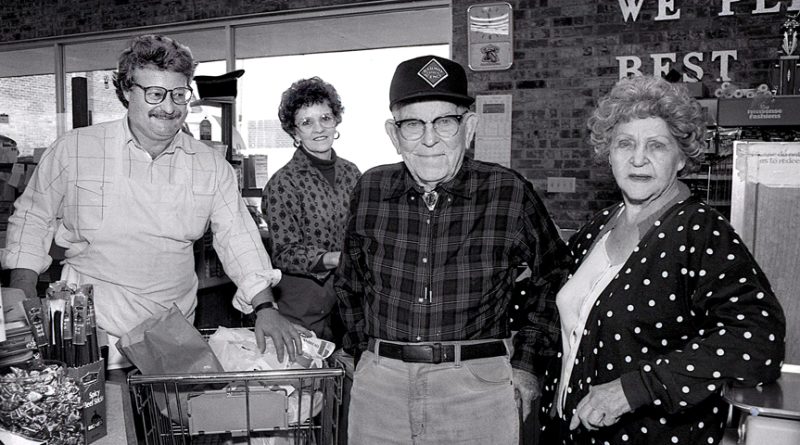

One-time Wells Fargo driver Spearman recalled grandmother’s tale of Civil War Georgia

From East Texas Journal, February 1994

By Hudson Old, Journal publisher

A hundred and thirty-one years back, less a few months, Robert Spearman wriggled into the world over at Hunt County. His father was “a Georgia cracker,” still a babe in arms the day his grandmother held a shotgun on Sherman’s army and ordered the men off her porch.

“My grand daddy was off in the war and protecting the home fell to her,” Mr. Spearman said. “She told that soldier if he tried coming in she was gonna lift that hat off his head and she had both hammers back when she said it.”

The soldiers left the home alone. But they left with a team of dapple greys, the milk cows, and killed every hog, chicken and goose on the place. They took what they wanted from the barn and burned it.

“Daddy always told his mother that the day he was 21 he was leaving Georgia for Texas,” Mr. Spearman said. “He went to New Orleans and caught a train to Greenville.”

Along the way, the train made stops to allow passengers to stoke the fire under the broilers. Mr. Spearman settled at South Sulphur, between Greenville and Commerce, where he met and married a Miss Moody, formerly of Arkansas.

His father carpentered and the family farmed.

Mr. Spearman left the farm when he got a job driving for Wells Fargo in Commerce.

“I’ve wondered if there’s anybody else left alive who worked for the original old Wells Fargo line,” said Mr. Spearman, now 99.

To get 99 years in perspective, consider that at the time he retired, land in Franklin County was selling for $12 an acre along the edge of the blacklands at the Hopkins County line.

“We could have bought about anything we wanted out here for $12 an acre and picked prime land for $20,” he said.

He married Velma Hamilton, a Franklin County girl whose family goes back far enough that the little farm to which she and Mr. Spearman retired, fronts on Hamilton Road.

They met in Shreveport, where he worked as a freight agent after World War I. It happened that the home where he boarded belonged to her sister. Infatuated with a young girl’s love for a crusty old bachelor of 30-something, Velma set her cap and swept the playboy freight man off his feet.

The family worked and retired in Louisiana, raising two children there and never setting foot back in Franklin County until they were foot loose, career wise.

In January of 1965, they pulled up on the road fronting the old Hamilton family property, 111 overgrown thorny acres, once loved and farmed, but then forgotten and thorny.

“She took a look at it and said, ‘Come on, let’s go back home,'”Mr. Spearman said. “But I told her, just wait a minute. You know how cheap the taxes on this property are?”

They built a country-style cottage on the swell of a sloping crest, a home with a back porch and a tree swing just inside the backyard gate.

He found a tractor at Teague Motors –– “Might even have been old Mr. Teague’s tractor,” he said, and he set about the gentle-paced project of clearing the farm. He gardened some, and once a week, on Thursdays, they’d get out the Chevy and ride into Mt. Vernon.

Their extravagances included turning on the television a couple of times a day to watch favored programs and treating themselves to Sunday afternoon football. Mr. Spearman came by his conservative lifestyle honestly.

” I remember once going home after the war to visit my folks,” he said. “My mom had an $8 grocery receipt hanging on the wall.” He chided her for spending $8 in a month for groceries.

“That’s for the year,” she told him.

When the war came along, he and two other South Sulphur boys, Bill Turner and Tom Wilkins, were drafted.

After basic training he was shipped to Europe and spent seven weeks on the front before the war ended. Armistice day found him alone in the German border town of Thiacourt. Beside the road there, he rested, sitting on one of four fresh graves, something he’d never have thought of doing only a few weeks before.

But he’d grown accustomed to death, had grown used to the rattle of a machine gun against his hands. He’d served as a messenger for a while, living in useful fear as he traveled at night back and forth between the front lines and headquarters. He recalled one harried night when he rode a horse 32 miles across the black still darkness of France — remembered he and two other messengers who turned their tired mounts loose in a French meadow after finding bicycles for themselves. And he thought of it all as he sat, tired and sick, alone on a grave by the side of the road as the war officially ended.

After some weeks recovering in a hospital, he was discharged and returned to South Sulphur where he immediately searched out Tom Wilkins.

“What about Bill?” Mr. Spearman asked.

“Why he was killed,” Tom replied. ” I buried him myself with three others beside the road at Thiacourt.”

For nearly 80 years, Mr. Spearman’s wondered if he didn’t spend the final moments of World War I sitting on his friend’s grave.

Give life enough time, it seems, and it throws odd coincidences at you.

One windy night in Commerce, he listened to the steady flap of the Wells Fargo sign, beating against the awning in the breeze.

Annoyed, he got up and took the sign down, but before hanging it again, he wrote his initials on the sign’s bottom corner.

A half-century later, his Marine grandson was in California when he stumbled across an old Wells Fargo sign at a flea market. Remembering his grandfather, the soldier bought the sign and shipped it to Mr. Spearman. It hangs on his wall now, and down in the corner are the initials “RS.”