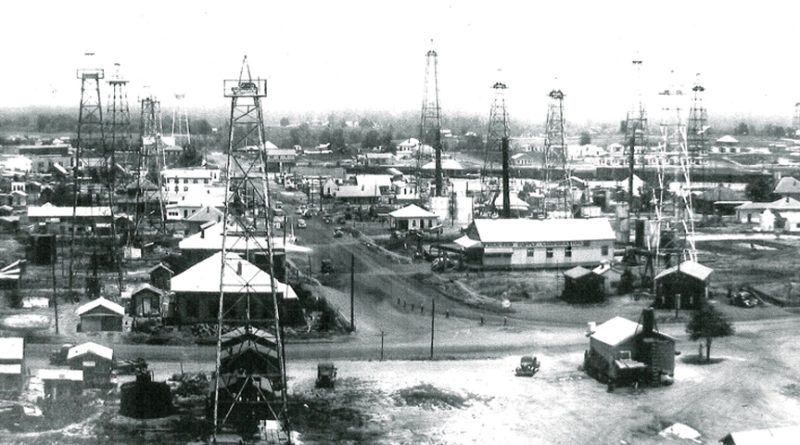

Oil strike turns Talco community into wide-open boom town

From East Texas Journal, February 1994

By Hudson Old, Journal publisher

Talco, Texas – The last oil boom in Texas gushed up here 79 years ago, and the newspapers took to lying about it right off the bat.

A dramatic account about the fear of fire made a pretty dazzling headline and a good story to boot in the beginning days of February, 1936. Horror stories of the fires in the field down in Rusk and Gregg counties made good copy in anybody’s paper and since there was now a well right here handy, it seemed to nearby periodicals that there oughta be some fear of fire here, too.

“Fire never was a problem here because this field never had the gas like the one down at Kilgore and Gladewater,” said John D. Wright. Within weeks of the strike, John D. and his daddy had brought mule teams from the Rusk, Gregg and Upshur County fields back to Talco and set up shop building well sites.

By the end of the second week of February, lease hounds had descended like locusts on the little farming community of 400.

“The town’s accommodations were taxed to the limits,” said the February 14, 1936 Mt. Pleasant Times Review. “Hundreds of people stayed up all night at the well” and jammed phone lines only added to the confusion.

In the summer of 1935, wildcat oilmen R.L. Preveto and Jno. B. Stephens teamed up to drill on the Charles M. Carr property about a mile east of Talco. They put together a 3,000-acre block of leases and began selling interests to Gulf, Humble, Tidewater and Magnolia. It wasn’t the easiest sell in town.

The nearest oil production was 60 miles away and the bottomland between the Sulphur River and White Oak Creek had been frustrating wildcatters for 20 years. But this well was set to go beyond the Woodbine formation at 2,900 to 3,100 feet. Peveto, Stephens, W.B. Hinton and W.F. Myer planned to take their well into the Paluxy formation nearly a mile beneath the surface. By the first of March, drilling veteran, Mike Langley announced that there was 760 feet of oil standing in the drill stem with the hole punched to 4,305 feet.

The late Mr. Stephens said the geologist originally staked the well several hundred yards north of the actual drilling site, at the foot of a long sloping hill.

It was muddy and the man moving in the rig said they’d never be able to get it out if they moved it to the foot of the hill, so drilling commenced at a handier spot on the top of the hill.

The C. M. Carr No. 1 was the northern most strike in the field.

In March of 1936, the community of 400 had a bank, two general stores, an undertaker and a drug store, a fourth class post office and a pair of diners.

“More than 3,500 persons live in the Talco area today,” reported the Talco Times on March 3, 1939. “Two refineries, several dozen oil companies, supply houses, pipeline companies and other firms are now numbered among Talco’s industrial achievements.”

Retailing wasn’t bad either.

“Suddenly everybody was working,” said Harold Bonham, who came to Talco within a month of the strike to work in the Jones-Kelley Drygoods store. “You never saw a man on the street looking for a job.” Cotton and corn were still cheap, but for Talco, the depression ended overnight.

Originally a sawmill man from Idabell, Okla., J.R. Wright took his four teams of mules to the Rusk County oilfields when Dad Joiner’s well came in 1931. The Sunday after graduating from high school in 1934, John D. Wright went to work for his father.

Pay for oilfield labor ranged from 20 to 50 cents an hour. J.R. Wright’s “camp” was a tent town, as were the camps of the other 15 contractors with mule teams, all busy building well sites.

Joe D. Hughes, who did work on Humble Oil’s leases, was the biggest contractor with 150 mules.

John D. worked briefly as a guard in a pipe yard.

“I’d run the thieves out of one end of the yard, and they’d come right back in the other end,” he said.

Within a month of the strike, the town incorporated. The population explosion created health problems — rain turned the streets to mud, and wagons buried to the axles in drag, Mr. Bonham recalls.

The city floated bonds to build a $200,000 water and sewage system, a $25,000 city hall and $125,000 worth of paved city streets.

By April of ’37, reflect the minutes of a town council meeting, there was “a general complaint” among citizens about the owners of beer parlors, vagrants and other persons of questionable reputation to loiter about said places of business for the purpose of plying their trade.”

“There was a honkytonk on about every corner,” Mr. Bonham recalls.

Mr. Bonham and Elmer Cato, the police chief, went undercover one evening after a saloon girl stole a dress from Mr. Bonham’s dry goods store.

They tracked down their suspect at a local bar.

” I wasn’t much of a dancer, but I went in and asked her to dance,” Mr. Bonham recalls. “She was wearing the dress and I asked her if she wanted to go outside.”

Once outside, the damsel found herself in the company of the police chief, Mr. Bonham’s wife and his father-in-law.

“We got as good a cussing as I’d ever had,” Mr. Bonham laughed. “And we got the dress back.”

The girl turned out to be a runaway from Sulphur Springs and the chief had her folks come pick her up.

Meanwhile, the town council legislated some moral guidelines, making it “unlawful for any female person to accost any male person for the purpose of making any improper or indecent suggestion . . .”

Almost, but not quite likewise, town fathers made it unlawful for any male person to unnecessarily accost females, leaving us to wonder the conditions under which it became necessary to accost a female in Talco in 1937.

Itinerant merchants, peddlers, vaudeville shows, traveling surgeons and physicians and medicine show men flocked to the town.

There was the problem of men from the oilfields bathing “naked” in public places, an item addressed by the town council in June of ’36.

By March of ’37, said the Paris News, business at the post office had sky rocketed pieces of mail daily before the strike to 10,000 to 15,000 pieces daily.

Postmaster Farris A. Brown was quoted as saying that he’d formerly slept half the time on the job for lack of something to do, but with the increase in business, he didn’t “have time to sleep half the night.

There was a brief media war.

Beginning in the ’20s, a woman named Kate Moore published a small newspaper called The Talco Record from one room in her home.

A week after the strike, Sam Holloway established The Talco Times. The Record died. The March 3, 1939 edition of the Times was 48 pages.

Each month, the town’s payroll and bills filled a single-spaced typewritten page for everybody from the printers to the blacksmith.

Annual licensing fees for various professions were established, pouring cash into the city treasury and to some degree insulating established merchants from competition.

Foot peddlers paid $2.50 while a peddler with one horse or team of oxen paid $3.50. Peddlers with two horses or two teams of oxen paid $5 and anybody riding into Talco with plans to sell clocks or washing machines paid $125, a fee not applied to existing clock and washing machine retailers. By 1939, there were 683 working wells here — nearly two for every person who’d lived in the community before the strike. Tax revenue from the oilfields made dreams that had seemed impossible only months before become reality.

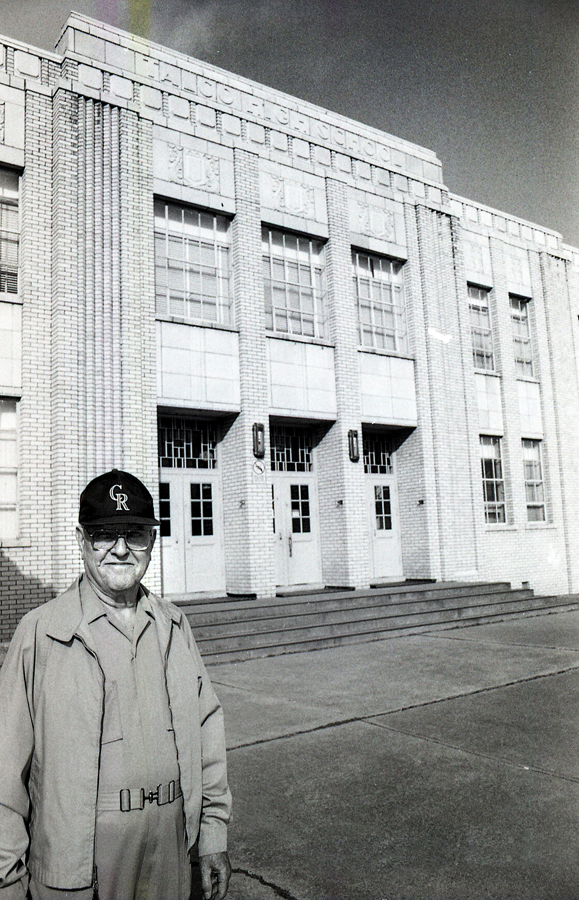

When Mr. Wright’s father died suddenly in 1937? he found himself holding the reins of his father’s business.

He briefly moved the operation to the Marion County oilfields but came back to Talco to do excavation work when citizens voted to spend $185,000 on a new school.

He used his mule teams to log and when the oilfield began expanding to the west toward Hagansport, he went back to building well sites.

It was a hard life. For five years he lived in tent camps. Rain and mud were continual problems.

“We were working on the Rutherford lease one morning and by 9 o’clock we had five teams bogged down,” Mr. Wright said. Pits to hold drilling mud were still being excavated by mules pulling slips, but one innovative contractor had brought a dragline into the oilfields.

The day the mules bogged, Mr. Wright went to Dallas to buy a dragline. H.D. Burleson at the Browning and Ferris Equipment Company didn’t have a dragline that day, but he did have a bulldozer.

“I’d never seen a bulldozer before that day,” Mr. Wright went back to Felix Jones at the Talco bank to borrow the down payment. Since the only information Mr. Wright brought back was Mr. Burleson’s assurance that a bulldozer could dig a pit, Mr. Jones initially turned him down, sent him to Guaranty Bond banker Eugene Lilienstern in Mt. Pleasant.

” I found him at the drugstore and when I rattled off that $6,500 figure he about dropped out of his chair,” Mr. Wright said.

“He told me there wasn’t that much money in Titus County and sent me back to Mr. Jones,” Mr. Wright said. Finally, Mr. Jones agreed to loan him $1,000 and his mother-in-law loaned him another $550, money that brought the first dozer back to the Talco oilfield. It came with an operator.

“It might as well have been a rocket ship for all we knew about how to run it,” Mr. Wright said. His crew eyed the machine suspiciously as it clattered off the trailer.

Suspicion faded with every pass the dozer made.

“In two hours, the dozer’d done more work than we could have done in two weeks,” Mr. Wright said, and Wright excavation became an overnight in the Talco field.

Heavy equipment operators were about as plentiful as airplane pilots in those days. When the first operator returned to the equipment company after 10 days, Mr. Wright searched the state, finally finding an operator out of “west Texas.”

Drilling drifted from the prairies out toward Hagansport into the White Oak Creek bottomland to the north. Mr. Wright arrived at a well site to find his dozer buried and the operator disgusted with the mud.

“That dozer didn’t look like anything but a ball of mud,” Mr. Wright said, and the frustrated operator announced that he was headed back to West Texas where they had enough rock to hold a dozer up. Various men who drove Mr. Wright’s mules tried their hands and were generally stuck in two passes.

At a loss, Mr. Wright finally climbed on the thing himself.

“Sometimes, you look around and don’t find anybody but yourself to make do with,” he said, but make do he did. By the 60s, Wright excavation was running 25 dozers with the accompanying fleet of trucks and a shop, doing oilfield working building flood levies for the army corps.

The word in the oilfield in those early days was that the boom would peter out in five years, Mr. Wright said. The newspapers authoritatively gave the field a 20-year life. Nearly 60 years later, the oil’s still coming, but considerably slower.

Originally called Gouldsboro, the farming community first made the map when the Paris and Mt. Pleasant railroad came through.

The post office was established, and in 1912 a Mr. Lovelace, then the postmaster, got orders from the postal service to change the name of the post office because it was being confused with the town of Goldsboro. According to oral tradition, a fellow named Jim Brown came up with the name “Talco” while sitting in the general store with Mr. Lovelace. Spotting a bottle of Talcum powder next to a second bottle turned so that only the letters “CO” appeared on the label, Mr. Brown said, “Why don’t we call it Talco?” And they did. Melea Goodroe wrote about it in her English IV research paper at Rivercrest High School in 1975. Melea’s research is treasured enough locally that Rusty Jones, grandson of old-time banker Felix Jones, kept a copy of it down at Talco State Bank, where he was the president.

In her “History of the Talco School,” a 1962 college theme paper, Thelma Jones told a similar story about the post office mandate.

“This notice threw Mr. Lovelace into a state of panic. Dallas Fry, Everett Lewellin and J . H . Brown was in the store where the post office was located and tried to help Mr. Lovelace,” she wrote.

“One of them, seeing ‘Talco Candy Company’ on a packing box under the counter suggested Talco’. The name was sent in and accepted.”